Background

Craniofacial Anomalies (CFAs) are among the most common human birth defects and have considerable functional, aesthetic, and social consequences.1,2 Each year, approximately 295,000 infants succumb to congenital anomalies, with the majority of these anomalies involving a diverse array of structural and functional abnormalities of the head and facial areas.2–5 Clefts of the palate and lips are commonly reported form associated with CFA occurring in 1 out of every 700 live births.4

In low-resource countries like Uganda, there is a significant dearth of information regarding the presentation, management, and outcomes of children with CFAs. Compounding this issue is the lack of accessible Craniofacial Surgeons and adequately equipped Craniofacial units, which hinders the provision of appropriate care and support for these children.6–8 Moreover, studies have indicated that children with craniofacial anomalies are often stigmatized, with some associating their condition with superstitions such as divine punishment or witchcraft.9–11

We report therefore, three cases of children born with CFA at Kiruddu National Referral Hospital. We aim to create awareness to the public about presentation and management challenges of children with CFA but also to inform policy makers to set priorities tailored in supporting children with this condition in low resources countries including Uganda.

Case 1

The case involves a 3-week-old female baby who was delivered at term with several craniofacial anomalies. The baby had a complete bilateral cleft lip, an incomplete defect in the left 1/3 of the lower lip, and a complete defect of the palate with a tag on the right nasal side wall. Additionally, there were wide-set eyes, a small mandible, absence of the left external ear, and a normal canal. The child experienced difficulty in suckling and breathing when breast milk was given. The parents had limited education and occasional alcohol intake but no reported family history of CFA or other congenital malformation.

The child was diagnosed with Goldenhar syndrome, a syndromic craniofacial anomaly, along with a differential diagnosis of Treacher Collins syndrome with facial clefts, bilateral complete cleft lip and palate, and nasal pyriform aperture stenosis.

Due to financial constraints and limited diagnostic techniques, sophisticated investigations have not been performed. The planned treatment involves orthodontist intervention, lip repair at the age of 3 months, cleft and Tessier repair at 9-12 months, and left ear reconstruction between the ages of 6 and 10 years, although the child has not yet reached the appropriate age for these specific operations. Figure1

Case 2

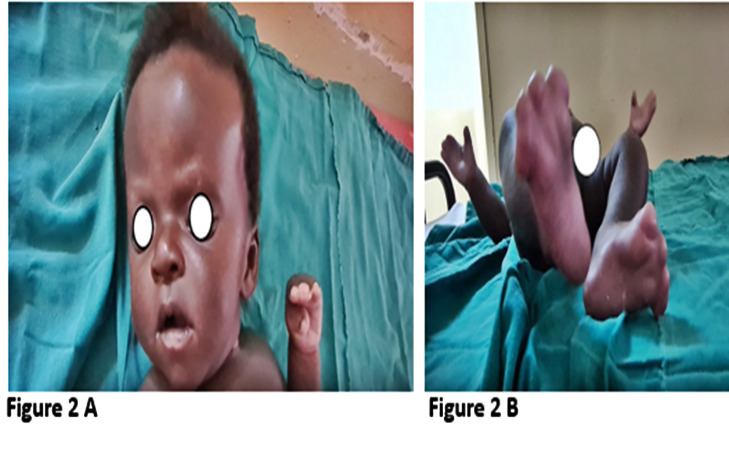

The case involves a one-month-old male child who was born with multiple deformities affecting the head, fingers, and toes. The baby was delivered via Caesarian section post-term, weighed 3.7kg, and required oxygen support for four hours after delivery. The child is the fifth born to a 26-year-old mother and 34-year-old father. The mother received prenatal care, including iron and folic acid supplementation, antimalarial medication, and tetanus toxoid. There is no history of a CFA or other congenital malformation in the family, and the other four siblings are healthy. The baby breastfeeds well, and was brought to the hospital for the repair of hand and feet deformities.

Physical examination revealed a high peaked frontal head, midface hypoplasia, exophthalmos, spoon and mitten fingers and toes (bilateral), a high notched palate, and medial bending of the interphalangeal joint of the thumb finger bilaterally. The diagnosis of Apert syndrome, characterized by mitten or spoon fingers, a high peaked forehead, a high arch, and hypertelorism was made. (Figure 2)

Case 3

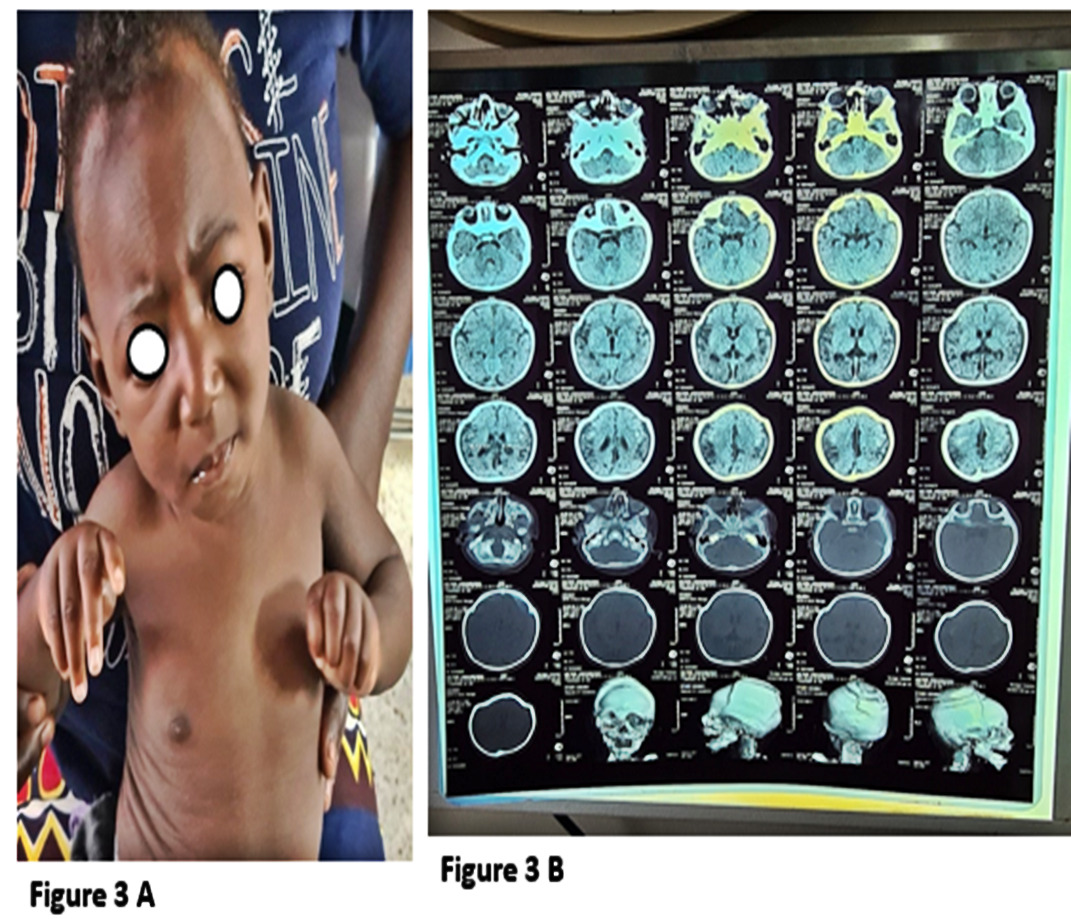

The case involves a 6-month-old male child who presented with an abnormal head shape since birth, accompanied by abnormal limb movements, finger fixed in a flexed position, hearing impairment, delayed milestones, and poor weight gain. The child is the third born and was delivered by Caesarean section at term, with delayed crying and the need for resuscitation. The mother received prenatal care starting at 12 weeks gestational age and made six visits, receiving folic acid, Tetanus toxoid, and unidentified malaria treatment. There is a family history of similar abnormalities in the paternal grandmother and great grandfather, with fingers fixed in flexed positions.

The child’s parents are refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with no history of alcohol or substance use. The other two siblings are unaffected. The child was referred from Mulago neurosurgical center with a diagnosis of coronal craniosynostosis and was planned for multidiscipline team approach lead by Plastic and Reconstructive surgeons. Clinically, the child was in fair condition, able to breastfeed, with a symmetrical face but with coronal depression affecting the frontal bone, which was underdeveloped compared to the temporoparietal bones. The left hand had flexed fingers. Computed tomography scans confirmed metopic, coronal, and sagittal fusion, leading to leading to a diagnosis of metopic craniosynostosis (Carpenter syndrome). The child did not undergo surgical correction due to the unavailability of a craniofacial surgeon and craniofacial unit, and there was no screening for syndromic causes due to limited molecular diagnostic techniques in the local setting. (figure 3)

Discussion

We present three cases of children with craniofacial anomalies (CFA) who were treated at Kiruddu National Referral Hospital. The first case involves a child with Goldenhar syndrome, the second case The first case involves a child with Goldenhar syndrome, the second case is a child with Apert syndrome, and the third case is a child with metopic Craniosynostosis (Carpenter syndrome). The standard approach to describing CFA includes both physical and clinical observations. However, the comprehensive evaluation of these patients requires sophisticated investigations such as CT scan, abdominal ultrasound, echocardiogram, and electrocardiogram (ECG). Unfortunately, these investigations were not initially conducted due to financial constraints and the lack of genetic typing service in our setting.

Among the reported cases, only the one with metopic Craniosynostosis (Carpenter syndrome) had a reported family history. This is consistent with the most studies on craniofacial anomalies (CFA) that occur sporadically, possibly due to new mutations.5,12 As observed in our case series, craniofacial anomalies (CFA) typically manifest with a combination of deformities affecting the extremities, neck, heart, and abdomen, in line with previous research findings.13 None of the three cases showed any evident risk factors for CFAs, highlighting the need for further investigation into the etiology and pathogenesis of congenital craniofacial anomalies in our setting. Unfortunately, the lack of advanced molecular diagnostic techniques hampers our ability to identify and understand many craniofacial disorders, leaving them unknown.1 Nevertheless, majority of the congenital body defects still have no known causes established, most cases do occur sporadically, influenced by genetic and environmental factors such as smoking, alcohol use , pre and post conception folic acid use, among others.14–16 Effective management of children with craniofacial anomalies (CFA) necessitates a comprehensive, coordinated, and culturally sensitive approach to care. However, our case series and similar studies have revealed a significant lack of easily accessible specialized and coordinated care to address the unique challenges faced by these children, particularly in low-resource countries.17

Although no obvious risk factors were identified in any of the three cases, the lack of improved molecular diagnostic techniques in our setting hampers our ability to further understand the causes and mechanisms underlying congenital craniofacial anomalies. As a result, many craniofacial disorders remain unknown and require further investigation for a comprehensive understanding of their etiology and pathogenesis.

Conclusion

This case series provided valuable insights into the three cases of craniofacial anomalies, but it is important to note that the follow-up for these cases was limited. As a result, the specific details regarding the long-term management and outcomes of these individuals remain unclear. While the initial diagnoses and treatment plans were established, the comprehensive assessment of their progress and the effectiveness of the interventions were not fully documented. Further research and more extensive follow-up studies are necessary to gain a comprehensive understanding of the management and outcomes for individuals with craniofacial anomalies in resource constraints settings. Establishing a safe and effective service for craniofacial anomalies in a national referral hospital requires assembling a multidisciplinary team, creating dedicated facilities, and providing continuous training for healthcare professionals. This training can be facilitated through national and international exchange programs, including workshops and on-site visits by experts from high-income countries.