Introduction

Chronic rheumatic valvular heart disease is the leading cause of cardiovascular death in developing countries. In 2015, it was estimated to affect more than 30 million population in those countries, and it is the main indication of open-heart surgical procedures.1,2 In contrast, coronary artery disease is the main cardiovascular pathology and indication for cardiac surgical operations in developed nations. The valvular diseases in those countries are mainly related to age-related degenerative processes and they tend to have concomitant coronary artery disease (CAD) justifying the recommendation for routine screening among those patients preoperatively. Some centers reported that the majority of patients who had aortic or mitral valve surgery needed concomitant coronary procedures due to significant coronary obstruction.3

Among patients presenting with symptomatic aortic stenosis, concurrent CAD occurs in over 50 % of those over 70 years of age and over 65 % of those over 80 years of age.4Contrary to that, due to the difference in the pathophysiology of rheumatic valvular heart disease and socioeconomic factors, CAD is rare among the patient population. But because of the lack of strong study on this issue, we have been following the AHA recommendation of screening all patients above 40 years of age with Chronic rheumatic valvular heart disease (CRVHD) requiring surgery for incidental CAD preoperatively, although the guideline recommends even lower age at 35 years for screening cutoff age if patients have strong risk factors.5 For this reason, we decided to evaluate the results of coronary studies among those patients who had surgery at our hospital from January 2017 to October 2023.

Methods

Study design

This is a retrospective study done by reviewing the patients’ admission and operative charts looking for the reports of coronary studies, the valve(s) affected, and procedures performed from January 2017 to October 2023 at Tenwek Hospital, a training mission hospital performing the majority of open-heart surgery in Kenya and East African region. Ethics approval was obtained from the hospital’s institutional ethics and research committee.

Inclusion criteria-Patients aged 40 years and above, with rheumatic valve disease.

Exclusion criteria: Age less than 40, all other causes of valvular diseases, including aortic aneurysm, degenerative disease, and symptomatic IHD patients with concomitant valve disease.

Data collection and analysis

The operative database was first screened and identified all patients who are 40 years of age or above and had open heart surgery due to CRVHD only, all other indications are excluded. The age at the time of surgery, gender, Body mass index (BMI), and comorbid diseases like Hypertension (HTN) and Diabetes mellitus (DM) were recorded. The valve lesions and the specific procedure (repair vs replacement) were documented. The coronary study results were checked and grouped as normal and abnormal. Basic descriptive statistics were done using PSPP and tables and graphs were generated using MS Excel.

Results

Our study captured 108 patients who met the inclusion criteria during the study period. The majority (n=75) were female and the mean age at surgery was 51yrs as indicated in Table 1.

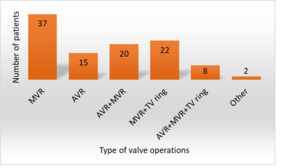

Isolated Mitral valve replacement was the most performed single valve operation (n=37) followed by Mitral replacement with Tricuspid ring annuloplasty(n=22). Combined Double or triple valve procedure accounts for almost half of the procedures(n=50) as shown in Figure 1.

Ninety-eight percent of patients had coronary studies either with CT coronary angiography (CTCA) or invasive coronary angiogram and results were reported for degree of calcification with calcium score and/or degree of stenosis of major coronary arteries. Only two patients had mild non-obstructing CAD identified and required no additional intervention (figure 2). The first patient was a female, 49 years old with hypercholesterolemia found in laboratory studies. The second patient was also female, 60 years of age with dyslipidemia and a BMI of 31kg/m2.

Among those patients, 17.4% of them had HTN, 3.6% were diabetic and 3.6% were known to have deranged lipid profiles in laboratory studies (figure 3). The prevalence of obesity or overweight was low among those patients and >50%of them had a normal BMI between 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2 as seen in Table 2.

Discussion

Valvular heart diseases often coincide with coronary artery disease (CAD) in older patients in Western countries, with varying prevalence rates across studies. For instance, Emren et al found significant CAD in 26.4% of Mitral stenosis patients and 57.7% of Aortic stenosis patients.6 Similar studies reported a high prevalence of CAD in Aortic disease (21.4%) and mitral valve disease (16.2%).7 Patients with aortic stenosis are more likely to have concomitant disease.8This association is attributed to the pathophysiology of valvular diseases, leading to degenerative calcification that also affects coronary arteries. The prevalence of CAD is influenced by conventional risk factors such as hypertension, male gender, dyslipidemia, smoking, and the type of valve lesion.7

In contrast, rheumatic valve disease, a consequence of acute rheumatic fever’s abnormal immune reaction to streptococcal pharyngitis, has less impact on coronary vessels. Despite being the leading cause of cardiovascular deaths in children and young adults in low-middle-income countries, rheumatic valvular heart disease typically progresses to heart failure without significantly affecting coronary arteries.9

Unlike age-related degenerative heart diseases, which involve calcification of heart valves and a high prevalence of concomitant coronary artery disease, patients with isolated rheumatic valve diseases have a lower likelihood of having significant coronary disease. Studies have reported higher CAD prevalence in degenerative aortic valve disease, non-rheumatic etiology, patients over 60 years, smokers, hypertensive and diabetic patients, and those with angina.3,10

Our study concurs with findings from Brazil by Kruczan et al., indicating the rarity of concomitant CAD among patients with isolated rheumatic valve disease.11 Most of our patients, predominantly from low socioeconomic status, exhibit fewer risk factors for CAD than populations with higher economic status. Notably, hypertension was the most common comorbidity (17.4%), while diabetes and dyslipidemia were uncommon (3.6%), and smoking was not reported.

Screening for CAD in valve disease patients preoperatively can identify those with significant coronary stenosis requiring concomitant coronary artery intervention. For example, a study by Boudoulas et al reported that the majority of patients who had mitral or aortic valve procedures underwent CABG at the same time at Ohio State University Medical Center between 2002 and 2008.3

While current ESC and ACC/AHA guidelines recommend coronary evaluation for valve surgery patients12,13 Our study questions the applicability of these guidelines to rheumatic heart disease populations, where the prevalence of concomitant CAD and valve lesions is lower. Our findings suggest that for isolated rheumatic valvular heart disease, routine CAD screening can be safely avoided for patients with minimal or no risk factors, minimizing financial burdens and avoiding surgery delays.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study sheds light on the nuanced relationship between rheumatic valvular heart disease and concomitant coronary artery disease (CAD) in older patients. The findings underscore the rarity of significant CAD among those with purely isolated rheumatic valvular heart disease. Our study adds valuable insights, suggesting that routine screening for CAD in patients with isolated rheumatic valvular heart disease may not be necessary for most individuals without significant risk factors. This not only avoids unnecessary financial burdens on patients but also mitigates the risk of delayed surgeries that could be potentially lifesaving.

Limitations

It is crucial to acknowledge the limitations of our study. Being retrospective, it is susceptible to observational biases, and the absence of some essential data, such as lipid profiles in certain cases, may impact the completeness of our findings. Additionally, the challenge of patients seeking coronary studies at different hospitals and not returning with the results introduces an element of uncertainty.

Recommendations

We recommend future prospective studies with a larger and more diverse sample to further elucidate these associations and contribute to refining clinical guidelines for this specific patient population.

Competing interests

We declare there are no conflicts of interest regarding this paper’s publication.