Background

Burn injuries represent a substantial global public health challenge with an estimated 180,000 fatalities annually.1–3 Most of these incidents occur in low- and middle-income countries, with significant concentrations in regions such as Africa and Southeast Asia, as reported by the World Health Organization.4,5 In 2019, the burden of burns, quantified in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), amounted to a staggering 7,460,448.65 with 67% of this burden attributed to years of life lost (YLLs) and 33% to years lived with a disability (YLDs).3–6

Burn injuries have widespread and profound implications (both physically and psychosocially) and significant socioeconomic consequences.7,8 Cooking-related burns have been identified as a particularly debilitating subset of burns with long-term consequences that distinguish them from other etiologies.1,9 A study conducted in Nigeria by Belie et al revealed a heightened prevalence (estimated at 14.1%) of burns arising from cooking gas explosions.10 Additionally, a separate study by Marc et al underscored the notably higher mortality rates associated with gas-related burn incidents compared to those from other causes.11

In countries such as Indonesia and India, there has been an increase in liquefied petroleum gas (LPG)-related burn injuries. The transition to LPG as a primary energy source has been accompanied by a surge in burn incidents, and a 5-year retrospective study in Indonesia vividly portrayed this trend. The majority of cases involved middle-aged males, frequently occurred in domestic settings, and were often attributed to LPG leakage. These incidents have resulted in major burn injuries, frequently accompanied by inhalational injuries, which emphasizes the urgent need for government regulations and preventive strategies.7,12

Within the specific context of Rwanda, the country’s focus on achieving Sustainable Development Goal 7, “Universal Access to Clean Modern Energy,” is evident in its efforts to increase household LPG adoption. The National Master Plan aims to significantly increase LPG adoption rates, with the government envisioning a transition from a usage rate of 5.6% in 2020 to 13.2% and 38.5% by 2024 and 2030, respectively.13,14 Although this transition to cleaner cooking fuels has the potential for health, social, and environmental benefits, there are also expected increased burn risks associated with LPG use.15

Research has not comprehensively examined burn injuries related to cooking gas explosions and their complications in patients in Rwanda. This study aimed to describe injuries associated with LPG use at the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali.

Methods

Design and setting

This study employed a retrospective design to review the patient charts and medical records for data collection. This study was conducted at the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali (CHUK), which houses the only specialized burn unit in Rwanda. This study focused on patients admitted with burn injuries related to gas explosions between January 2018 and December 2023.

Participants

All patients admitted to CHUK with gas explosion-related burn injuries were included in this study. Clinical data were extracted solely from the patient medical files. For cases with incomplete records, attempts were made to contact patients or their caretakers/family members via phone numbers documented in patient’s charts to understand the incident-related data including the type of gas cylinder and causes of the accident. Verbal consent was obtained prior to conducting interviews to gather missing data. Records of the rationale for obtaining verbal consent were maintained to ensure compliance with ethical standards.

Data collection

Data collection was performed by a trained team comprised of one medical student and three plastic surgery residents who were educated in appropriate data-collection techniques. Data were gathered via a structured questionnaire hosted on the KoboToolbox platform.16 The questionnaire consisted of three sections:

-

Demographic Information: Age, sex, educational background, and occupation,

-

Incident-Related Data: Circumstances surrounding the gas explosion, including the location, type of gas cylinder, and cause of the accident,

-

Clinical findings and outcomes: Total body surface area (TBSA) affected, site of injury, presence of inhalation injury, length of hospital stay, complications, and patient outcomes (mortality or recovery).

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using JMP software version 17.17 Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics, incident data, clinical findings, and patient outcomes. A multivariate linear regression analysis was used to identify variables predicting recovery or death outcomes.

Results

Demographic information

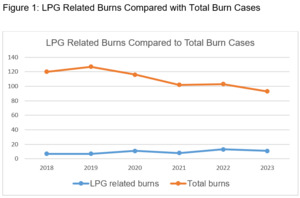

Between January 2018 and December 2023, 609 patients with burns were admitted to the CHUK burn unit: 57 (9%) of these patients experienced gas explosions and were included in this study. The sex distribution was nearly equal, with a slight male predominance (51%, N = 29) compared with females (49%, N = 28). The median age of the participants was 28 years (IQR: 19–34.5), with the majority (60%, N = 34) falling within the 18–35 years age group. Most patients were from Kigali (70%, N = 40), and a significant proportion had a primary education (49%, N = 28). The percentage of LPG burns in relation to other burns admitted to CHUK increased from 6% in 2018 to 13% in 2023 (Table 1; Figure 1).

Incident details and clinical findings

Most LPG burn incidents occurred at home (58%, N = 33), primarily because of gas leaks (53%, N = 30) and cylinder blasts (42%, N = 24). The median TBSA was 25% (IQR: 19.5–36.5). The depth of the burn was predominantly superficial partial thickness (61%, N = 35) and deep partial thickness (32%, N = 18). The head and neck regions were the most frequently affected (82%, N = 47), and 16 patients (28%) presented with inhalation injuries. The median length of hospital stay was 16 days (IQR: 7–32 days) and the overall mortality rate was 16% (N = 9) (Table 2).

Univariate analysis of factors affecting survival

Univariate analysis revealed no significant differences in survival according to sex (P = .673), province of origin (P = .738), educational level (P = .721), occupation (P = .091), location of injury (P = .693), burn mechanism (P = .656), or cooking gas tank size (P = .969). However, the factors affecting mortality included the depth of burn (P = .0016) and inhalation injury (P < .0001) (Table 3).

Linear regression analysis

In the multivariate linear regression analysis predicting recovery vs death among LPG-related burns, age, length of hospital stays (LOS), and association with inhalation injuries were identified as significant predictors. Older age was associated with decreased odds of recovery (ß = -4.851, P = .0008), whereas longer LOS (ß = 9.765, P < .0001) and absence of inhalation injuries (ß = 69.171, P < .0001) were strongly associated with improved recovery outcomes (Table 4).

Discussion

This study highlights the significant burden of LPG-related burn injuries among patients admitted to CHUK. These findings provide critical insights into the epidemiological profiles, mechanisms of injury, clinical outcomes, and predictors of recovery or mortality in this patient population. These results contribute to the existing knowledge while also highlighting the urgent need for targeted interventions to address the growing incidence of LPG-related burns among burn patients consulting CHUK.

The increase in gas explosion-related burns from 6% in 2018 to 13% in 2023 reflects the broader adoption of LPG in Rwanda as part of its transition to cleaner energy to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 7.13 These findings are consistent with studies from other countries transitioning to LPG (such as Indonesia and Nigeria) where an increase in LPG adoption was correlated with an increase in LPG-related burn incidents.3,10,12A retrospective study in Indonesia reported that most LPG-related burns occur in domestic settings due to gas leaks; this is similar to our findings, which highlight the need for preventive measures.12

The majority of patients in our study were young adults aged 18–35 years, comprising 60% of the cases, which is consistent with the findings from studies conducted in Nigeria and Indonesia.10,12 This age group is central to Rwanda’s workforce, which makes the socioeconomic impact of LPG-related burn injuries particularly profound. The people in this age group frequently handle cooking and related household tasks especially in urban areas where LPG usage is high, which increases their exposure risks. Moreover, many people in this age group manage food businesses, which increases their interactions with LPG cylinders and stoves. This demographic’s risk of LPG-related burns highlights the socioeconomic impact of such injuries and necessitates targeted safety education and preventive measures.

In addition, the fact that 49% of the patients had only primary-level education could be justified by statistics showing that people who have completed higher education are less likely to use LPG. Moreover, this finding may reflect the general educational landscape of Rwanda, where primary education remains the highest attainment level for a significant portion of the population. Limited education could contribute to a lack of awareness regarding safe LPG-handling practices as documented in the Indonesian studies.12 Public health campaigns aimed at raising awareness and improving safety practices are crucial for these vulnerable populations.

Gas leaks (53%) and cylinder explosions (42%) were the predominant causes of burns with injuries predominantly affecting the head, neck, and upper extremities owing to their proximity to the source during cooking. This finding is consistent with studies from low- and middle-income countries, in which similar injury patterns have been documented.10,12,18 A median TBSA of 25% and a high incidence of inhalation injuries (28%) are notable risk factors that contribute significantly to the mortality rate (16%), which are similar results to the study done in Tanzania.19

Our study findings highlight age, burn depth, and inhalation injury as key predictors of outcomes. Older age was associated with death, while longer hospital stays and the absence of inhalation injuries increased the chance of recovery. These findings correlate with other research emphasizing the impact of these variables on patient outcomes.3,10

Based on our research findings, the increase in LPG-related burns and severity of the injuries necessitate an immediate public health action. Educational programs focusing on safe LPG handling, the early detection of gas leaks, and the proper installation of gas cylinders should be reinforced. The use of trained professionals in the installation of LPG systems, including testing for leaks, can significantly reduce the risk of gas explosions (as recommended in China) and effectively mitigate the risks associated with LPG use.3 Rwanda, as it continues to promote LPG as a cleaner energy source, should adopt similar preventive measures to reduce the incidence of LPG-related burns and ensure that the transition is both sustainable and safe.20

Future research should focus on several key areas to build upon the findings of this study. Intervention studies are required to assess the effectiveness of public health campaigns aimed at reducing LPG-related burns. Such studies could evaluate whether educational programs on safe gas handling can lead to a measurable reduction in burn injuries. Additionally, longitudinal cohort studies could explore the long-term outcomes of burn survivors by including their psychosocial impact, rehabilitation needs, and quality of life.

There is also a need to create and apply burn prevention policies that encourage public education, safe LPG use, and stronger safety rules. Future research should evaluate national burn treatment guidelines to ensure patients receive consistent evidence-based care. Studying how these policies and guidelines affect patient outcomes could help to reduce burn injuries and improve long-term recovery.

Moreover, it would be beneficial to conduct cost-effectiveness analyses to assess whether implementing preventive measures, such as gas-leak detectors or subsidies for safer cooking appliances, would be financially viable and impactful in reducing the burden of burns. Finally, efforts should focus on enhancing the available regulations and initiatives for LPG cylinder testing and distribution to ensure that safety standards are enforced across the country.

Limitations

This study has several limitations to consider when interpreting the results. First, the retrospective nature of the study introduced the possibility of recall bias, especially in patients whose medical records were incomplete. Although efforts have been made to contact patients or their families to fill in missing data, inaccuracies may still exist. Second, the relatively small sample size of 57 LPG-related burn cases limits the generalizability of our findings to other regions or settings in Rwanda (especially the rural areas) where LPG use may be less prevalent. Third, the study included patients from CHUK, which may not reflect the national landscape of gas explosion-related burns. Finally, detailed documentation regarding the exact time from injury to initial medical intervention was often lacking, and information about pre-existing comorbidities was inconsistently recorded. Consequently, we did not account for these potential confounding factors that could influence patient outcomes.

Conclusion

LPG-related burns are prevalent in CHUK and associated with poor outcomes, especially among young patients. This study highlights that even if LPG is widely recognized as a source of clean energy, it can lead to devastating burn injuries with severely poor outcomes. This highlights the need for improved safety measures and increased public awareness of proper handling and use to mitigate these risks. Future research should focus on exploring effective preventive interventions while also assessing long-term outcomes of burn survivors. As Rwanda continues to transition to LPG use as a cleaner energy source, it is of paramount importance that this shift is accompanied by comprehensive safety protocols that protect the well-being of the population.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the CHUK Institutional Review Board (reference number EC/CHUK/071/2024).

Informed Consent

Verbal consent was obtained from the participants or their guardians before the interviews were conducted to fill in any missing data. Documentation was maintained to justify the use of verbal consent and patient confidentiality was maintained throughout the study.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Dr Thierry Cyuzuzo, upon reasonable request. Access to the data may be subject to institutional or ethical approval to ensure confidentiality and responsible use.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no competing interest.

Funding

None declared.