Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, disrupted health care systems worldwide, suspending or deferring elective surgical procedures to conserve resources and control virus transmission.1 Elective surgeries represent a large portion of hospital surgical admissions and operations. The cancellation of these surgeries created a significant backlog that led to significant patient distress and poor clinical outcomes for patients with chronic conditions, putting immense pressure on the health care system once restrictions on elective surgeries were lifted.2

Suspension of elective surgeries due to the pandemic significantly affected patients and health care systems. Elective surgeries represent up to 60% of hospital surgical procedures, and their postponement delayed critical interventions for patients with non-life-threatening but progressively debilitating conditions such as malignancies, cardiovascular disorders, and musculoskeletal diseases.3,4 Delayed surgeries led to disease progression with attendant complications in several patients, necessitating more complex procedures when operations resumed.5 Moreover, hospital revenue streams were heavily affected by suspending elective procedures, further straining resources already reallocated to managing COVID-19 patients.6,7

Reintroducing elective surgeries became a priority for hospitals globally as health care systems adapted to the pandemic. However, resuming these procedures required weighing the risk of nosocomial COVID-19 transmission with the growing need to address the surgical backlog. Many health authorities developed stringent guidelines for safely resuming elective surgical procedures, incorporating COVID-19 testing and vaccination, personal protective equipment (PPE) availability and usage, and careful patient selection criteria based on factors such as age, comorbidities, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification.8

Resuming elective surgeries during the pandemic presented several challenges, including concerns about the risk of virus transmission during hospitalization and surgery. Nosocomial infections, particularly during the perioperative period, have been associated with increased patient morbidity and mortality. Patients undergoing surgery in the presence of COVID-19 infection had worse outcomes, including higher postoperative pulmonary complications and longer hospital stays.9 Additionally, operating room staff faced higher risk of exposure, especially during aerosol-generating surgical procedures.10 Efforts to reduce these risks included preoperative COVID-19 testing, vaccination, and delaying surgery for those who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.11 Moreover, surgical protocols were modified to include enhanced infection control measures, such as limiting the number of personnel present during an operation, using advanced PPE, and optimizing the ventilation system.12

ASA classification, a system used to assess the physical status of patients preoperatively, played a critical role in selecting patients for elective surgeries during the pandemic. ASA class is a valuable tool for predicting the perioperative risk, and the higher the class (ASA II or III), the higher the postoperative complications rate, particularly in the presence of COVID-19 infection.13 On reintroducing elective surgeries, many guidelines recommended prioritizing healthier patients (ASA class I or II) to reduce the likelihood of adverse clinical outcomes.14 Recent studies suggest that the resumption of elective surgeries should be closely guided by local hospital resources, particularly intensive care unit (ICU) availability and resources for managing potential COVID-19 surges.15

The resumption of elective surgeries during the pandemic raised significant ethical issues. Prioritization of patients for surgeries, considering the risks and health care resource constraints, has been under extensive debate.16 Clinicians have had to weigh patient safety against the need to provide timely interventions for those with non-COVID-related disorders. Prolonged delay of elective surgeries could change treatable conditions into more complicated or life-threatening situations.17 These ethical dilemmas highlight the need for clear, evidence-based guidelines for surgical prioritization, ensuring that patients with urgent conditions are treated while maintaining a safe, practical pathway to minimize COVID-19 transmission.18

This study addresses a critical gap in the literature evaluating safe resumption of elective surgical services during the pandemic in hospitals classified as resource-limited, using Kassala Police Hospital in Eastern Sudan as an example. Previous studies have predominantly focused on well-resourced settings,19 while our study highlights the unique challenges faced by hospitals with limited infrastructure, staff shortages, and sociopolitical constraints. The study highlights that patient selection and strict adherence to adapted infection control guidelines was essential for resumption of elective surgical services during the pandemic. The protocol included preoperative COVID-19 testing, adoption of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS), and optimum ICU capacity management, resulting in favorable postoperative outcomes for morbidity, mortality, and postoperative COVID-19 infection. Our study findings offer a practical approach for similar settings to safely reintroduce elective surgery in the COVID-19 pandemic.20,21

Methods

This retrospective observational study was conducted at the Department of Surgery at Kassala Police Hospital in Kassala state, Eastern Sudan, during the pandemic between July 2020 and January 2021. The hospital had 120 surgical beds serviced by 2 consultants, 3 specialists, and 6–10 residents. To avoid selection bias, we conducted a total sampling of 1292 patients who had complete medical records and were admitted for elective surgical procedures after reintroducing the regular elective surgery within the study period. We developed a questionnaire and validated it by using content and expert validation. The questionnaire comprised sociodemographic and clinical data. Data were collected from patients’ records and through phone calls to patients with missing important information, including patients’ demographics, comorbidities, and postoperative outcomes. Patients with incomplete records with major missing information and patients who were not contactable 3 times in 3 different days to complete minor missing data were excluded from the study. The phone calls were made by a trained registrar, who followed a structured format to ensure precise data collection. Variables collected included patient age, age group, gender, diagnosis, operative procedure, ASA class, comorbidities including diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, and ischemic heart disease (IHD), and the outcomes: ICU admission, hospital stay, postoperative morbidity and mortality, and whether the patient developed COVID-19 infection after admission.

All patients admitted within the study period were included to avoid selection bias. The ethics and research committee of Kassala Police Hospital approved the study under the code sp/25/3/2020/01, and the study was carried out in accordance with the regulations and principles of the updated Helsinki Declaration of 2013 for medical research. All patients gave informed consent to participate in the study, and written informed consent was obtained from minors’ guardians. All patients were deidentified before analysis to ensure confidentiality. All patients were notified that participation is voluntary and they can refuse to participate or withdraw at any time without changing their treatment plan or postoperative care and follow-up.

Protocol of Elective Surgery Resumption

The approach to resuming elective surgical services involved strict adherence to World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations and other guidelines, including using masks, social distancing, disinfectants, and virtual communication. A committee comprised of representatives from various departments ensured effective communication and coordination for the resumption of elective surgery. High-risk groups such as people with diabetes were given open paid leave until further notice, regular screening of staff was conducted, and those who tested positive were isolated. We modified perioperative procedures and preparation to conform with WHO guidelines to ensure the safe reintroduction of elective procedures. Standard sterile techniques were reinforced with additional infection control measures. The surgical staff adhered to PPE protocols, and nonintubated patients had to wear masks intraoperatively. The 120-bed surgical ward was rearranged to ensure adequate spacing and designated COVID-free zones were established to minimize cross contamination. COVID-19 vaccination was provided for the surgical staff and general population. The patient was required to be asymptomatic and test negative in order to have an elective procedure. All symptomatic or confirmed COVID-19 patients had their surgeries scheduled after 2–4 weeks of resolution based on their symptoms and indications for surgery. We incorporated ERAS to minimize hospital stays. Separate ICU facilities were designated for surgical and COVID-19 patients. Furthermore, innovative postoperative care and follow-up were emphasized using phone calls, photographs, or video call messaging platforms.

Statistical Analysis

For data analysis, we used SPSS version 26.0. A descriptive analysis was performed using mean ±SD for all continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Chi-square and T-tests were used for bivariate analysis. P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

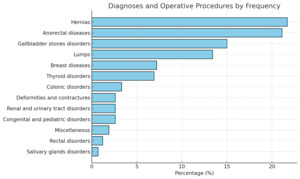

During the study period, a total of 1292 patients were admitted for elective surgical procedures. The cohort included patients ranging in age from 6 months to 71 years. A summary of demographic and clinical characteristics is presented in Table 1, and the distribution of diagnoses and surgical procedures is illustrated in Figure 1.

Key outcomes

Postoperative complications were observed in 43 patients (3.3%), while 4 patients (0.3%) died in the postoperative period. COVID-19 infection occurred in 11 patients (0.9%), and ICU admission was required for 20 patients (1.5%). The majority of patients (65.4%) were discharged within 1 day of surgery, whereas 1.4% required hospitalization for more than 10 days. Notably, only 3.1% of patients had documented comorbidities, including DM (1.16%), hypertension (1.24%), and IHD (0.7%). These findings highlight a generally low rate of complications and infection, possibly reflecting the effectiveness of preoperative screening and perioperative care protocols during the COVID-19 era.

Significant predictors of outcomes

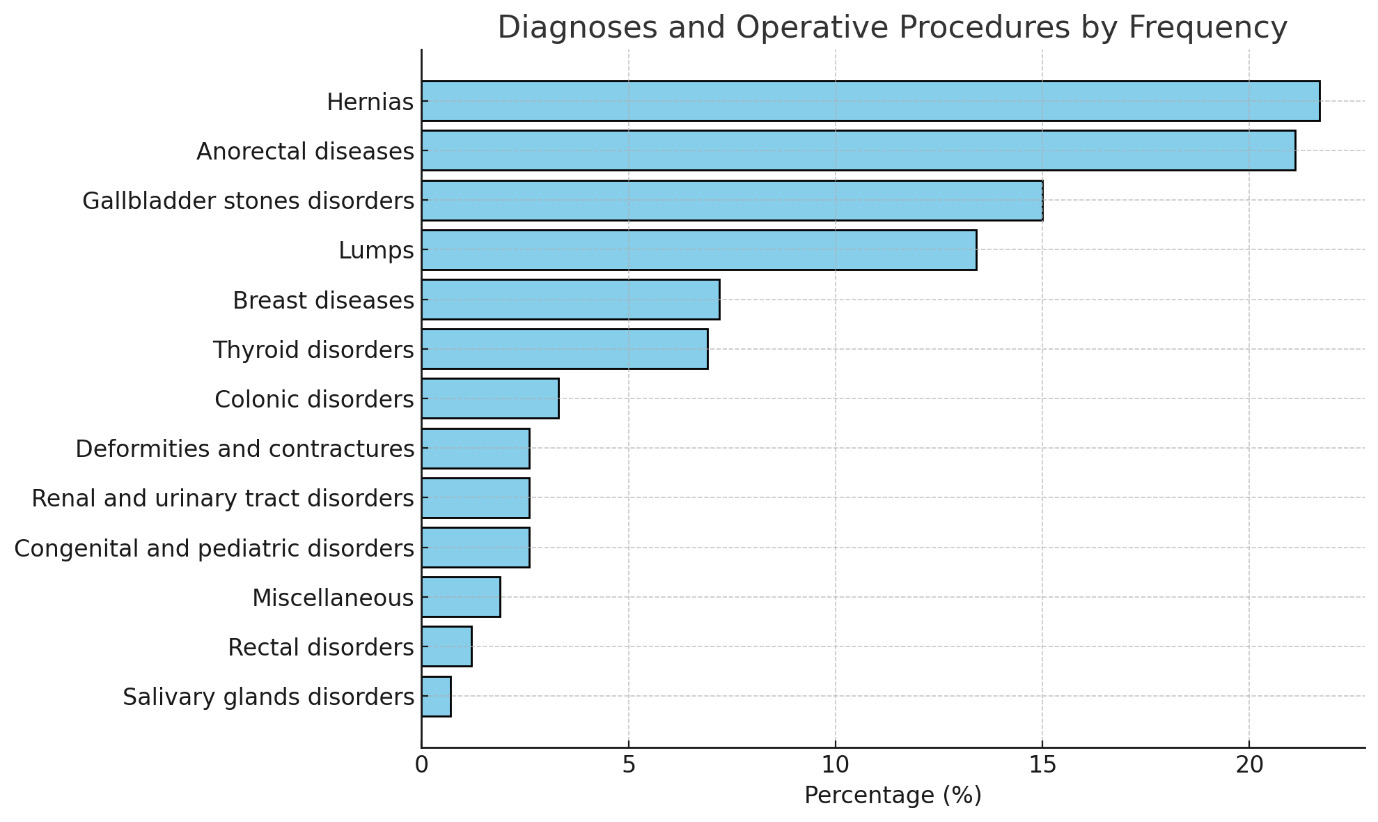

Advanced age, higher ASA classification, and the nature of surgical diagnosis and operative procedure were all independently associated with adverse postoperative outcomes, including prolonged hospitalization, ICU admission, morbidity, mortality, and postoperative COVID-19 infection (P < .001 across all comparisons).

-

Age emerged as a strong predictor across all measured outcomes, with older age groups demonstrating increased rates of morbidity, mortality, ICU admission, COVID-19 infection, and extended hospital stays,

-

ASA class was similarly influential: higher ASA scores were significantly associated with longer hospitalizations, increased postoperative complications, ICU admission, and mortality,

-

Surgical diagnosis and procedure type had a statistically significant effect on all outcomes, most notably on hospital stay duration (X2 = 3110.256, df = 36), reflecting the variability in postoperative recovery based on the complexity of intervention.

Gender and outcomes

Gender was not significantly associated with postoperative morbidity (P = .5), mortality (P = .3), ICU admission (P = .7), or postoperative COVID-19 infection (P = .9). However, there was a significant difference in hospital stay duration by gender (P < .001), suggesting that nonclinical factors may influence discharge timing.

Statistical correlations between patient variables and clinical outcomes are detailed in Figure 2, which highlights the significant influence of ASA classification, age group, and procedure type on postoperative risk, while confirming the limited role of gender in predicting most adverse outcomes.

Discussion

Elective surgeries resumption during the COVID-19 pandemic was a significant global challenge, particularly in resource-limited settings. The posponment of elective surgical procedures resulted in large surgical backlogs, increased emergency surgery presentations, and increasing morbidity, leading to more pressure on the already weak infrastructur of the health care systems.22,23 Our study of 1292 elective cases highlighted the risk factors and outcomes associated with performing elective surgeries under pandemic conditions in a low-resource hospital. These findings align with global reports on hospital capacity, infection control, and safe surgical practices during COVID-19.20,21

Other research indicating that the predictors of poor outcomes included older age and high ASA scores was reaffirmed in our study also resulting in increased morbidity, mortality, longer hospital stays, and higher ICU admissions.20,21 Our observed postoperative complication rate of 3.3% matches international reports of 2%–10% during the pandemic.24 Despite our rigorous protocols and procedures, 0.9% of patients developed postoperative COVID-19, emphasizing that infection control can reduce but not fully eliminate nosocomial risks.

Some local challenges including cultural and political and general safety issues impact the outcomes. The local impact of violence, infrastructure collapse, and cultural norms such as family insistence on accompanying patients delayed admissions and consent processes. These challenges are similarly seen in regions like Palestine and highlight how sociopolitical dynamics exacerbate surgical care delivery in crises.25

The pandemic revealed vulnerabilities in health care systems particularly in low-income countries, where shortages of staff and medical supplies were more pronounced. Nevertheless, our complication and mortality rates remained comparable to global findings, though slightly higher than prepandemic elective surgery rates.26 ICU admissions were closely linked to advanced age, high ASA class, and procedural complexity, aligning with global trends.27,28 The postoperative complications are shown in Table 2.

COVID-19 infection among our study population was significantly associated with older age and higher ASA scores (P < .001), reinforcing previous reports.29 In response, we adopted risk mitigation strategies to minimize hospital stay duration, hence reducing the risk of exposure, including day of surgery admission and ERAS protocols. Notably, 65.4% of patients were discharged within 1 day, and 29.2% stayed for 2–5 days.30

As part of the crisis management committee, the hospital administration, in collaboration with health authorities, ensured availability of PPE, diagnostic screening tools, and trained medical and health personnel which are key factors contributing to our favorable outcomes.23,31 Regarding surgical timing after COVID-19 infection, while global guidelines recommended a 7-week delay, our protocol followed a 2–4-week window for asymptomatic, test-negative patients, which still yielded safe outcomes.32,33

In contrast to some literature, our study did not find association between gender and increased morbidity, mortality, ICU admission, or COVID-19 infection. However, females had significantly longer hospital stays (P < .001), a finding that needs further investigations and is potentially linked to biological recovery differences.34,35

Robust infection control protocols are crucial to minimize the infection rate, as postoperative COVID-19 is associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates. In our cohort, despite precaution, 11 patients (0.9%) developed postoperative COVID-19, underscoring the ongoing risk of infection and the need for continued vigilance.36,37 Our findings offer a practical, adaptable framework for safe reintroduction of elective surgical services. They enhance the necessity of strong infection control, timely testing, careful patient selection, and collaborative hospital governance.38

Potential confounders in the study include unmeasured patient comorbidities, possibility of variable ICU access, and social determinants influencing COVID-19 exposure. Despite these factors, our results remain clinically relevant and in alignment with international reports on predictors of ICU admission and the complications of advanced age and ASA class.23,27

Despite shorter intervals (2–4 weeks) of postponment of elective surgery post-COVID-19 recovery differing slightly from recommendations to wait 7 weeks, our patients had favorable outcomes.32,33 Our outcomes are comparable with recent global studies on postoperative results during the COVID-19 era,39–47 as shown in Table 3.

Reports from low-resource settings support our approach and results. A systematic review emphasized changes in surgical patients prioritization and telemedicine during the pandemic,48 while COVIDSurg Collaborative research provided a framework for managing elective backlogs.49 Our protocol’s inclusion of repeat preoperative COVID-19 testing helped maintain a low infection rate (0.9%), aligning with findings from similar environments.50

Conclusions

Reintroducing elective surgeries during pandemics is feasible and safe in scarce-resource hospitals. Key factors to improving clinical outcomes include patient selection with careful consideration of ASA class and age, rigorous infection control protocols, and preparedness for ICU admissions. The more extended hospital stays for female patients and the persistent risk of perioperative COVID-19 infection highlight areas that require further study and interventions.

Limitations and Challenges

It is a retrospective observational study conducted in a single center, which makes its generalizability difficult or questionable. Although we tried to avoid selection bias by including all patients, it remains possible as some records were completed using phone calls. Religious and social beliefs needed tender, careful handling to avoid refusing COVID-19 protocols during the treatment process, and the team experienced administrative difficulty in implementing the protocol and procedures.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brigadier General Abdel Rahman Almadani Abdallah, the administrative director of the hospital, and Major Abdallah Mohammed Abdallah, head of the Director Executive office, for their support.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the research and ethics committee in Kassala Police Hospital.

Informed Consent

All patients who participated in the study or their guardians have given a written informed consent of participation.

Patients or their guardians gave written informed consent for publication of the study results.

Data Availability

The data are provided within the manuscript text and tables.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no competing interest.

Funding

None declared.