Background

Splenic abscess is a rare entity and has a 100% mortality rate when untreated.1 In autopsy studies, the incidence of splenic abscess ranges from 0.05 to 0.7%.1,2 It has a mean age of 41.3 ± 19.0 years with a female-to-male ratio of 1:1 with1,3,4 about 1 out of 4 being splenic abscesses ruptures.3 The commonest cause of splenic abscess is septic embolism arising from bacterial endocarditis. Other factors include trauma, metastatic infection, splenic infarction, gastrointestinal tract (GIT) perforation, pneumonia, and arteriovenous malformation.1,5 It usually occurs in immunocompromised conditions such as hematologic malignancies, diabetes mellitus, and pancreatic diseases.1 The organisms causing splenic abscess are bacterial (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, Salmonella typhi, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa),2,4 Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and fungus.2,6,7

A splenic abscess often presents as a triad of fever, tender left upper quadrant of the abdomen, and elevated leucocyte count.1,7 Fever and abdominal pain are the most common symptoms.2,3 Chest symptoms may occur in the presence of a left-sided pleural effusion or pyopneumothorax.6,7 Abdominal distension may occur, sometimes accompanied by splenomegaly.8 A patient may present with features indicative of the site of origin of the infection, in addition to clinical features of peritonitis.8 The diagnosis of a splenic abscess can be confirmed by ultrasound or a computed tomography (CT) scan.1 An abdominal CT scan with and without intravenous contrast confirms the diagnosis, identifies complications, and guides the management of splenic abscess.8 Management typically involves antibiotics,5 percutaneous drainage, and splenectomy.7 The management modalities depend on the patient’s clinical status, the number of abscesses/lesions (single or multiple), the size and location of the abscess, and local expertise.5,7 A ruptured splenic abscess could lead to pneumoperitoneum, peritonitis, sepsis, septic shock, left-sided pleural effusion, and death.4,8

The case report aims to demonstrate the use of a Foley catheter drainage in the management of a ruptured splenic abscess caused by E. coli and Klebsiella oxytoca.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old female was experiencing 1 week of abdominal pain in the left upper quadrant and left flank, vomiting, general body weakness, and abdominal mass/fullness in the left upper quadrant. The abdominal pain was exacerbated by movement. The past medical history was negative for diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and cardiac valvular disease. Surgical, gynaecologic/obstetric, and social history were unremarkable.

On examination, she had a temperature of 37.4°C, with a heart rate of 128, respiratory rate of 18, normotensive 129/89 mmHg, and oxygen saturation of 99%. The cardiorespiratory exam was non-revealing. The abdomen was tender in both quadrants, and splenomegaly was about 4 cm below the left costal margin. There were no classic abdominal signs of peritonitis.

The laboratory revealed mild microcytic normochromic anaemia 8.70 g/dL, leucocytosis (WCC 18.60 x 109/L), thrombocytosis 700 x 109/L, and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) 319. The biochemistry revealed potassium of 4.9 mmol/L, sodium of 137 mmol/L, elevated urea of 14.3 mmol/L, creatinine (329 µmol/L), and hypoalbuminemia of 25. The liver enzymes were normal. Malaria and Bilharzia tests were negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 10 mm/hr.

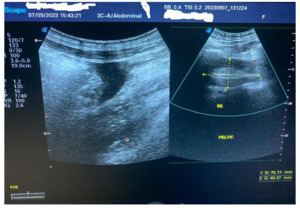

The ultrasound scan showed an enlarged hypoechoic spleen measuring 10.5 cm x 10.0 cm x 6.3 cm. Splenic infarct/abscess and hepatomegaly were detected. Echo-containing intra-abdominal free fluid (pus) with the deepest pocket was 62 mm. The left kidney was in the normal anatomical location, but the right kidney was in the pelvis (Figure 1). The CT scan was unavailable.

Pus revealed a Gram-negative bacillus, E. coli, and K. oxytoca sensitive to cefepime.

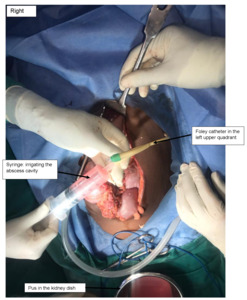

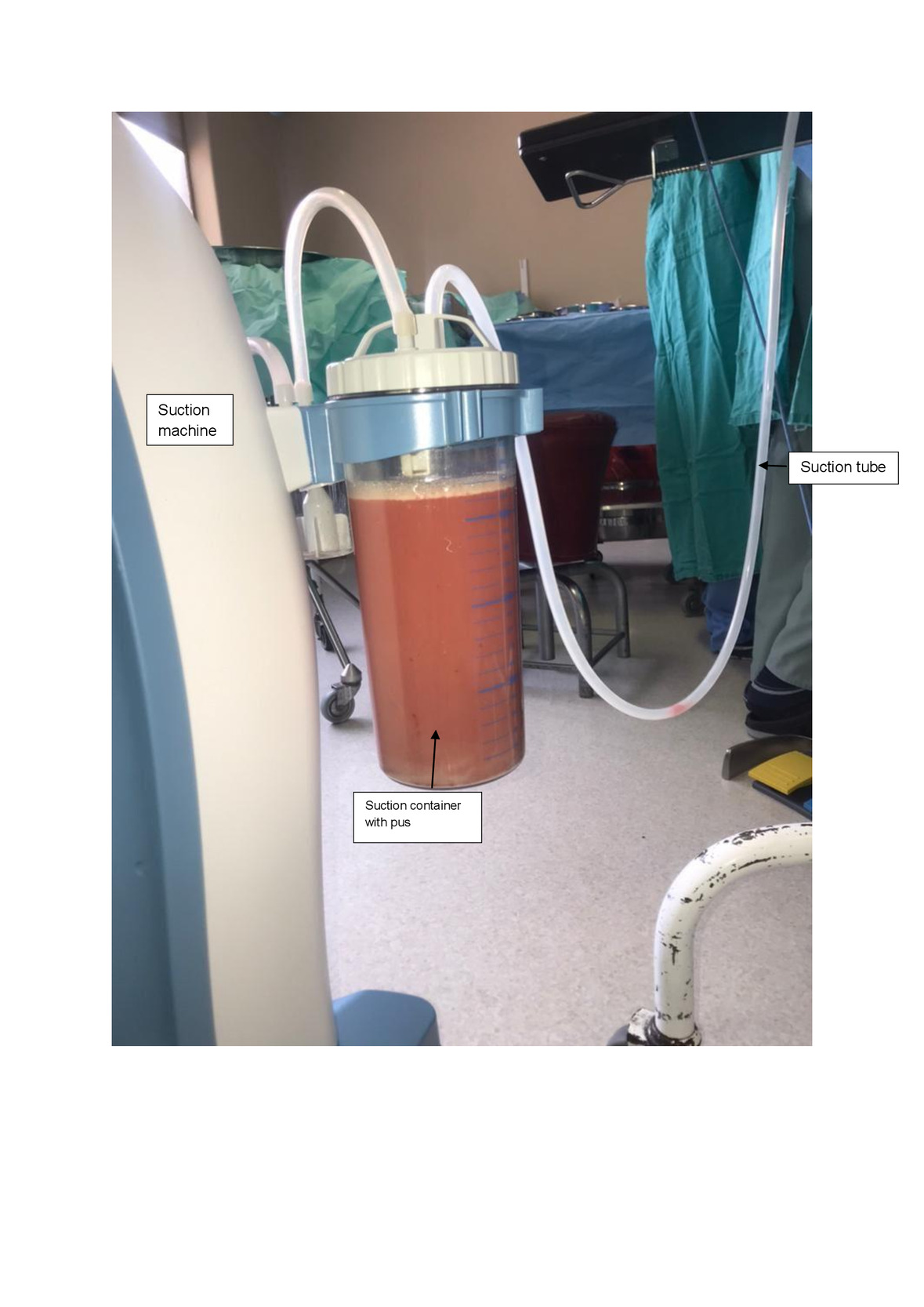

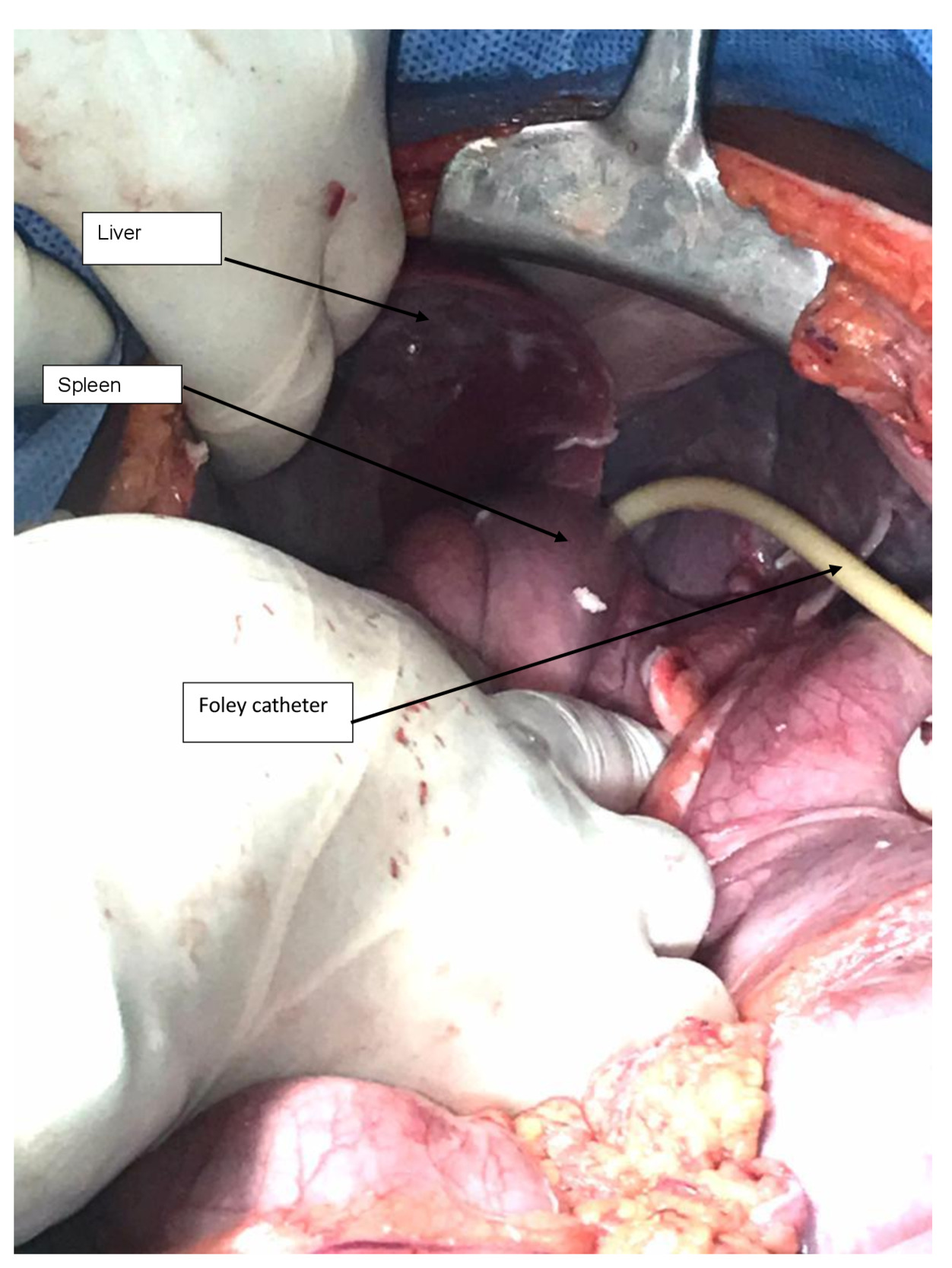

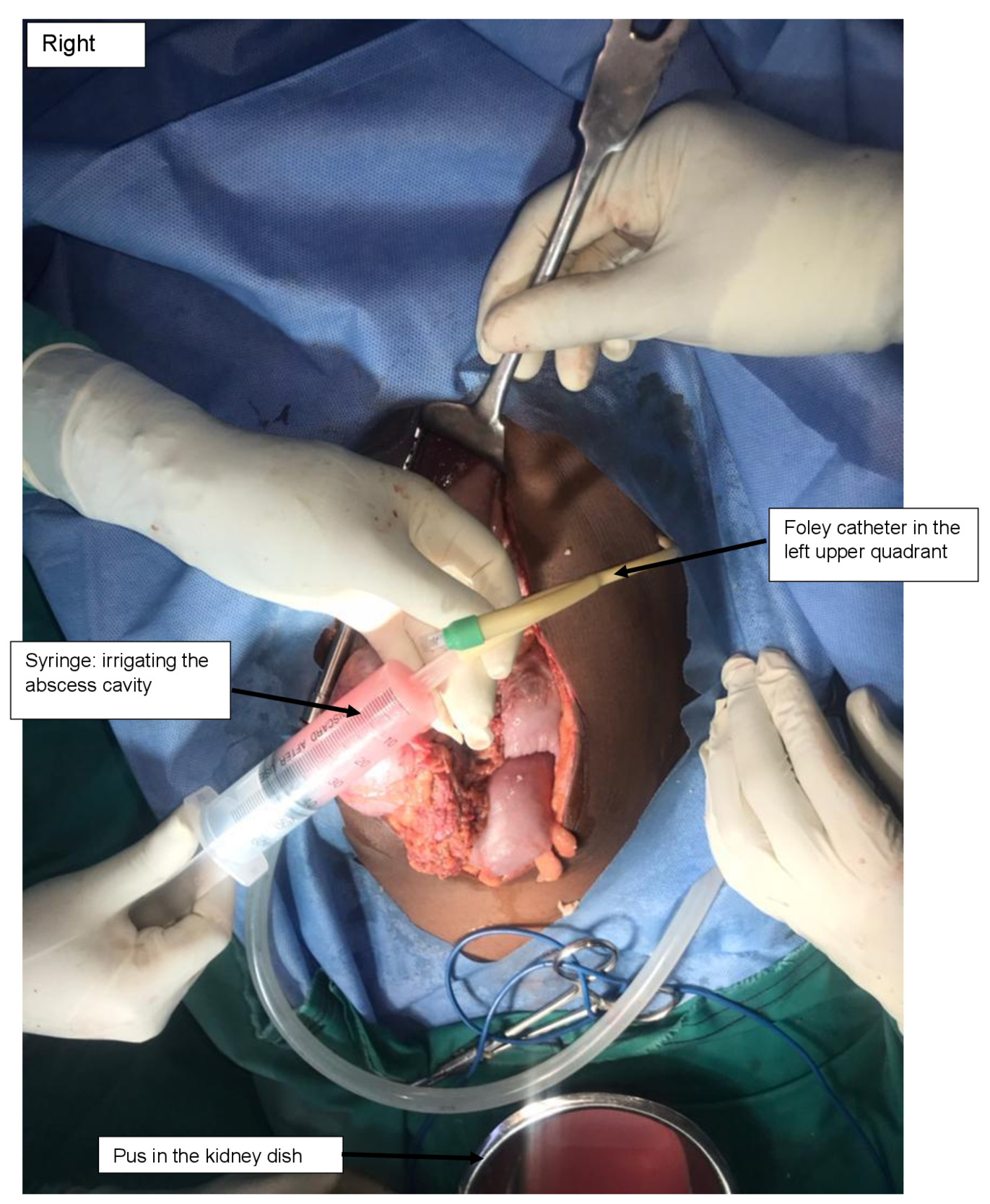

The patient was informed of the options of preserving the spleen (using available catheter drainage) and splenectomy with its complications. The patient consented to a laparotomy under general anaesthesia, and 2 L of yellowish pus were drained from the abdominal cavity (Figure 2). There was a single large loculated abscess in the superior pole of the spleen with a 1-2 cm opening on the superior border. The pus actively oozed out into the peritoneal cavity and was drained without debriding the spleen. The pus was drained with the readily available 14 French Foley catheter (Figure 3). The catheter was balloon-supported and secured to the skin in the left upper quadrant. The rest of the spleen appeared normal. The left kidney appeared enlarged, while the right kidney was not found in the normal anatomical position (ectopic pelvic kidney). Peritoneal lavage with copious amounts of warm saline and irrigation of the splenic abscess cavity were performed (Figure 4).

She was empirically placed on intravenous ceftriaxone 1 g twice daily and metronidazole 500 mg thrice daily for 5 days and then switched to cefepime based on the laboratory pus culture and sensitivity results for 5 days. The Foley catheter drained approximately 100 mL, 60 mL, 20 mL, and nothing on days 1 to 4, 5 to 6, 7 to 8, and 9 to 11, respectively. The Foley catheter was removed on postoperative day 11. The vitals (temperature 36.2°C and heart rate 83 beats per minute) normalized during the postoperative stay. She was discharged on day 13 on oral cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily to complete 2 weeks of antibiotics. During the postoperative period, kidney function test, WCC, and CRP levels normalized, and no follow-up radiology was performed.

Discussion

The diagnosis was a huge ruptured splenic abscess caused by K. oxytoca and E. Coli. Splenic abscess is rare, and rupture of a huge splenic abscess is even rarer. The patient had an incidental right ectopic pelvic kidney.

The mean age for developing a splenic abscess varies from 41 years to 50 years.2,7 However, our patient was 40 years old. Studies have contrasting reports on whether splenic abscess is common in males or females.2 An analysis of 16 cases in Taiwan found a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.7 The mortality rate for splenic abscess is varied across many studies (13% to 25%), but could approach 100% in the absence of treatment.2 Furthermore, it is higher in immunodeficient patients.7

The majority of ruptured splenic abscesses (70%) have been reported in immunocompromised conditions such as diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, hepatitis, chronic liver disease, pancreatitis, infective endocarditis, malignancy, and splenic trauma.2,7,8 In our case, there was no identifiable contagious or systemic infection/disease at the time of presentation except for the incidental right ectopic pelvic kidney (congenital anomaly).

In this case, the patient was experiencing left upper quadrant abdominal pain and fever, as supported by other literature.2 The classic triad of fever, left upper quadrant tenderness, and leucocytosis was found in most of the splenic abscesses.1,7,8 Furthermore, our patient had abdominal distention owing to the presence of 2 L of pus in the peritoneal cavity. However, she did not have classic features of peritonitis (diffuse abdominal tenderness, rebound tenderness, or involuntary muscle guarding of the abdomen) as expected in the presence of pyoperitoneum.8 As reported in other cases, our patient had splenomegaly.8 In patients with diaphragmatic defects, the intraabdominal pus may trek easily into the pleural cavity, resulting in pyothorax.6 In Taiwan, in a 5 year study, 50% of patients with splenic abscesses had left pleural effusions.7

In our case, the diagnosis was confirmed by ultrasonography. The ultrasound scan is cost-effective and non-invasive compared to the CT scan.6,8 Although some authors arguably claim that they have similar sensitivity.8 Using CT scans in a low-resource setting can be challenging and costly, however, both modalities are reliable diagnostic tools. Although the CT scan is the gold standard, it was not performed in our case due to non-availability.8 Concerning the radiographs, they are non-specific except in cases of splenic abscess with elevated left hemidiaphragm, pneumoperitoneum, and left hydropneumothorax.1,6,8

In our case, the ultrasonography, as well as laparotomy, identified a unilateral right ectopic pelvic kidney. Reports show that the majority of kidney anomalies are asymptomatic and commonly found in radiological investigations for urological and or other medical conditions, like in our case.7,8 The ectopic kidney sites include the pelvis (most common), iliac, lumbar, abdomen, or thorax, and can be unilateral or bilateral.9–11 Renal ectopia has male predominance, although in our case, the reverse was observed.9,11

In 80% to 94% of splenic abscesses, there is leucocytosis, as found in our patient.2,7 E. coli and K. oxytoca were isolated from the pus in our study. The array of isolated bacteria is varied among many studies and includes staphylococci, streptococci, salmonella, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Prevotella intermedia, Enterobacter cloacae, β-haemolytic streptococcus, Morganella morganii, and Proteus mirabilis.2,4,8 In our case, K. oxytoca was added to the list. In some reported cases of splenic abscesses, the causative organisms are not found, although fungus (Candida parapsilosis) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis have been found.2,6,7

The treatment arms embrace parenteral antibiotics, percutaneous drainage, and splenectomy.1,2 Generally, the patient is empirically started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and then definitive antibiotic therapy based on the microbiology and sensitivity pattern.5 Splenic abscesses treated with intravenous antibiotics have demonstrated variable outcomes with better outcomes as high as 82% and worse outcomes as high as 100%.7 However, when in combination with drainage and/or splenectomy, the outcomes are more desirable. Intravenous antibiotics (such as ceftriaxone and metronidazole) alone have been found to have good outcomes in patients with small and multiple splenic abscesses.7 In addition, the selection of antibiotics was guided by microbiology, sensitivity patterns, and local antibiogram studies. In our study, we used ceftriaxone and metronidazole with excellent outcomes. For those treated with antibiotics only, the mortality reaches 50% compared to percutaneous aspiration or catheter drainage (8.3%).3,7

Percutaneous drainage is inexpensive, less invasive than surgery, and an option for young patients who want to preserve the spleen.2 It could also be employed in critically ill or severely comorbid patients who cannot stand the stress of major surgery.2 Moreover, percutaneous drainage has been associated with lower mortality and complications.2

Splenectomy has been reported as the mainstay of treatment (90%), although other modalities have been employed with significant outcomes.8 Depending on the available services and expertise, a splenectomy could be performed via open surgery or laparoscopically. The laparoscopy approach entails a short hospital stay and quick recovery.1 Laparotomy for ruptured splenic abscess arguably eases adhesiolysis and abdominal lavage and has been performed with good outcomes.8 Splenectomy is reserved for failed drainage, recurrent splenic abscesses, and ruptured abscesses.1 It can also be considered when no adequate splenic tissue is left after drainage at laparotomy.2,8 However, it is more invasive and associated with bleeding/hematoma formation, thromboembolic complications, and immunosuppression.12

In our study, upon exploratory laparotomy, a huge ruptured splenic abscess with pyoperitoneum was found. The readily available 14 French Foley catheter was used to drain the splenic abscess and lavage. The use of catheter drainage is commendable in unilocular abscesses, non-septated abscesses, low-resource regions, and young patients, where you want to preserve the spleen.7 As such, a splenectomy was not done in our case. Furthermore, the high cost of the post-splenectomy vaccines, unavailability of prophylactic medications/vaccines, and poor patient education aided in guiding the option to preserve the spleen in this case.

This is a single retrospective case report, which limits its generalizability. Furthermore, limited documentation on huge ruptured splenic abscesses presenting with gross pyoperitoneum highlights the need for more clinical cases.

Conclusion

A huge ruptured splenic abscess is rare. The utilization of open surgery and Foley catheter drainage with definitive antibiotic therapy yielded excellent outcomes in ruptured splenic abscess caused by E. coli and K. oxytoca.

Informed consent/ethical approval

Written informed consent for submission and publication of this case, including imaging, was obtained from the patient. Patient privacy and confidentiality were maintained, and all patient identifiers were removed. Formal ethical approval was not required for this case report.

Data Availability

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Funding

No funding