Introduction

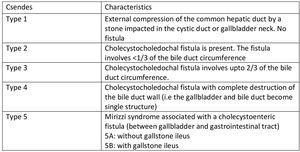

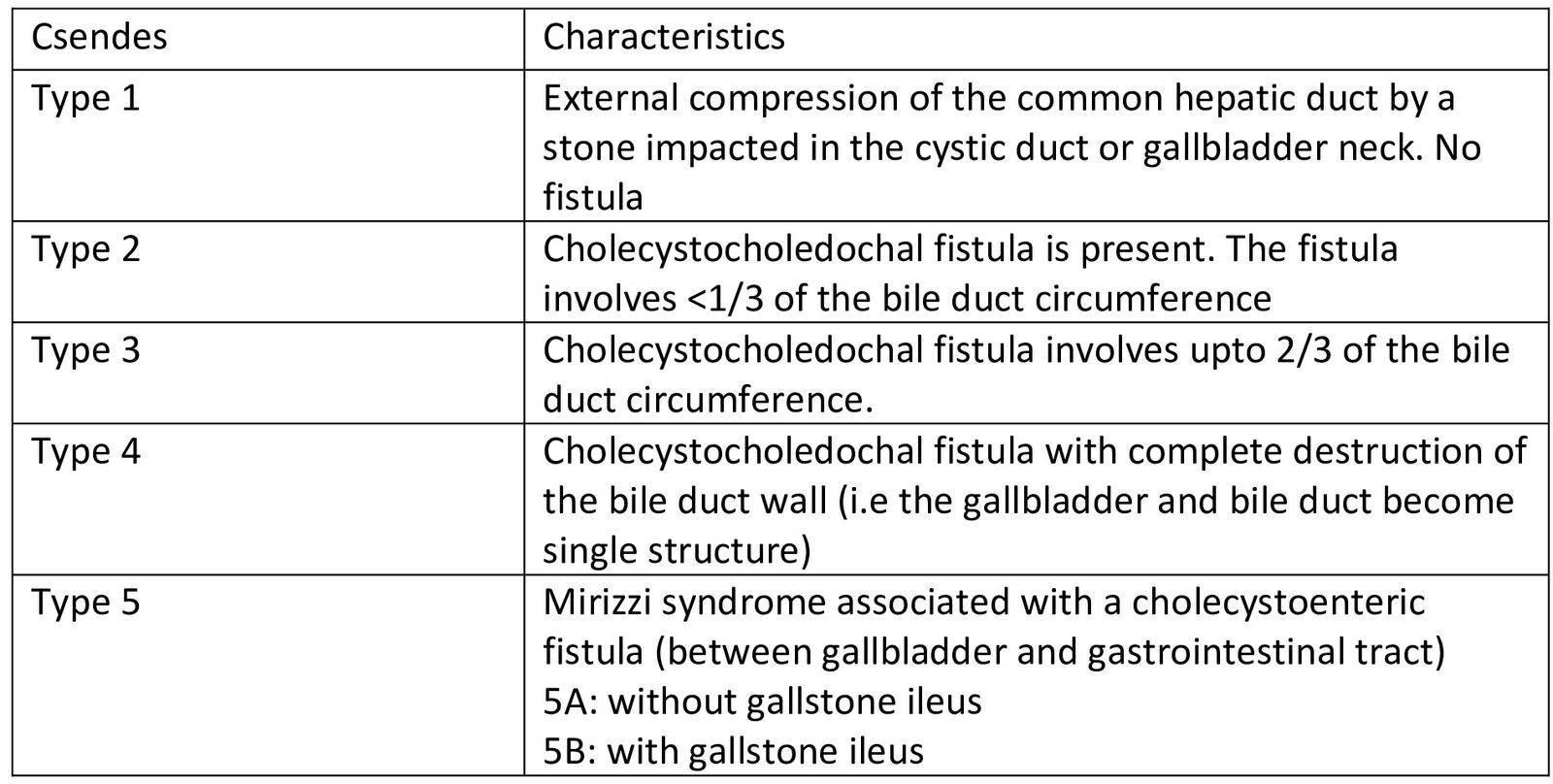

Mirizzi syndrome (MS) is an uncommon disorder brought on by external compression from impacted gallstones in Hartman’s pouch, which obstructs the common bile or common hepatic duct. While Hartman’s pouch is the commonest site of stone impaction, other known sites are the gallbladder neck and cystic duct.1 It is named after Pablo Luis Mirizzi, an Argentinean surgeon who first described it in 1940.1 It is an uncommon complication of chronic cholelithiasis. Mirizzi syndrome is uncommon, with an incidence generally less than 1% among patients with gallstone disease undergoing cholecystectomy, though rates may be higher in specialized centers or populations with longstanding or complicated gallstone disease.1,2 The Csendes classification is the most widely used system for categorizing MS. It describes five types based on the extent of common hepatic duct (CHD) or common bile duct (CBD) involvement by the impacted gallstone, as well as the presence and nature of a cholecystoenteric or cholecystobiliary fistula.2,3 An impacted gallstone causes a pressure ulcer, resulting in external compression of the main duct and eventually eroding into it. This inflammatory phenomenon describes the pathophysiological process leading to MS, at which point the disease may progress to a fistula, with varying degrees of contact between the bile duct and the gallbladder.4 MS poses considerable difficulties in diagnosis and management.

We sought to report a case of severe MS and highlight the challenges surrounding the diagnoses and management.

Case Presentation

We present the case of a 72-year-old female with a known history of well-controlled hypertension and asthma, both managed on regular treatment. She had no history of alcohol use, smoking, prior biliary interventions, or a family history of gallbladder disease. She presented with sporadic right upper quadrant abdominal pain over several years, gradual in onset, colicky in nature, and of moderate intensity, predominantly worsening at night. The pain was associated with anorexia and multiple episodes of bilious vomiting. She also noticed a progressive onset of yellowing of the eyes and dark urine, without associated pruritus or pale stools. She reported no history of weight loss, fatigue or chest pain.

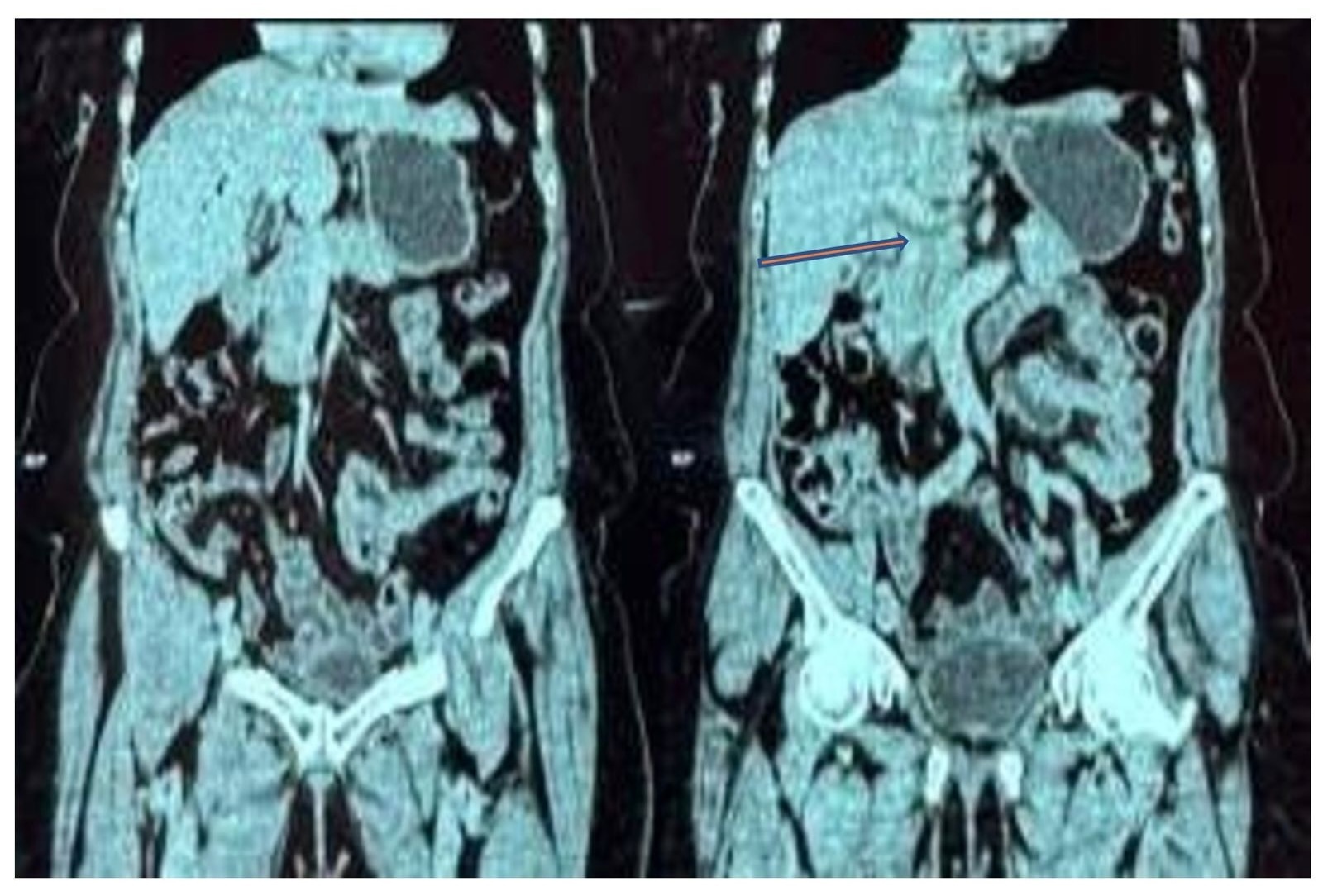

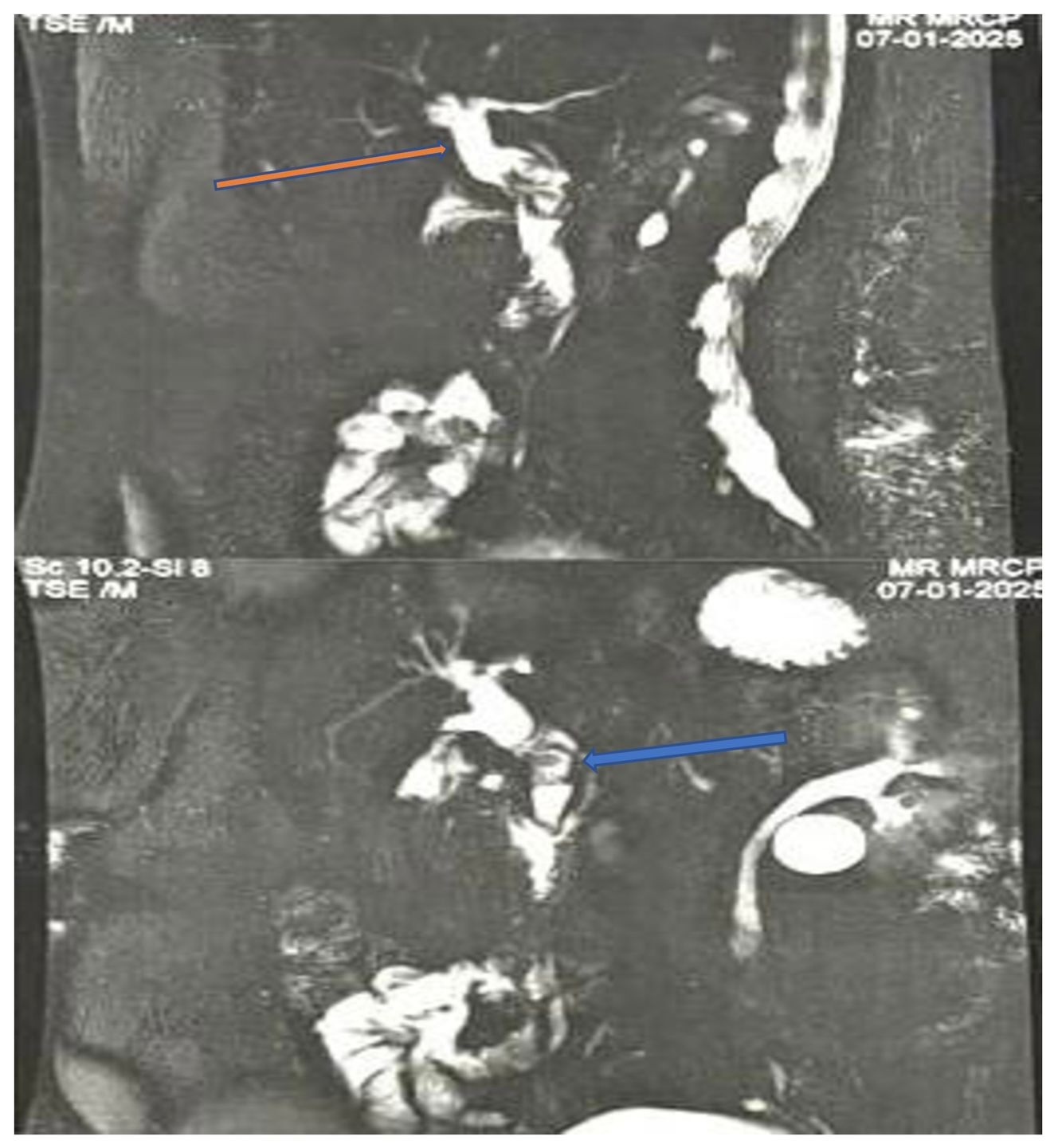

Following the persistence of these symptoms, she sought medical attention at a primary facility where some tests were done which showed leucocytosis of 14000/ul (4-10000/ul). A liver function test showed a cholestatic picture with ALP at 259 U/L (53-153U/L), GGT at 112U/L (11-52U/L), and direct bilirubin at 28U/L (0-5U/L). A Computed Tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1) done showed a thickened gallbladder wall measuring 3.5 mm with biliary sludge. There was mild intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary duct dilation with pneumobilia. The CBD measured 16.5mm and a tapering was noted in its distal portion. No stones were noted. These features were in keeping with acute-on-chronic cholecystitis. With a differential of acute cholangitis. A Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) (Figure 2) showed perihepatic collection, dilated CBD, and two lamellated calculi, measuring 9mm and 13mm, were identified in the proximal CBD, along with a distended, calculous gallbladder. A diagnosis of cholelithiasis with cholecystitis and obstructive choledocholithiasis was made. Subsequently, she was given intravenous antibiotics and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was done with CBD stone extraction and stenting. Three weeks later, her symptoms subsided and she was then referred to our facility for laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

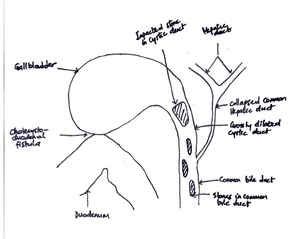

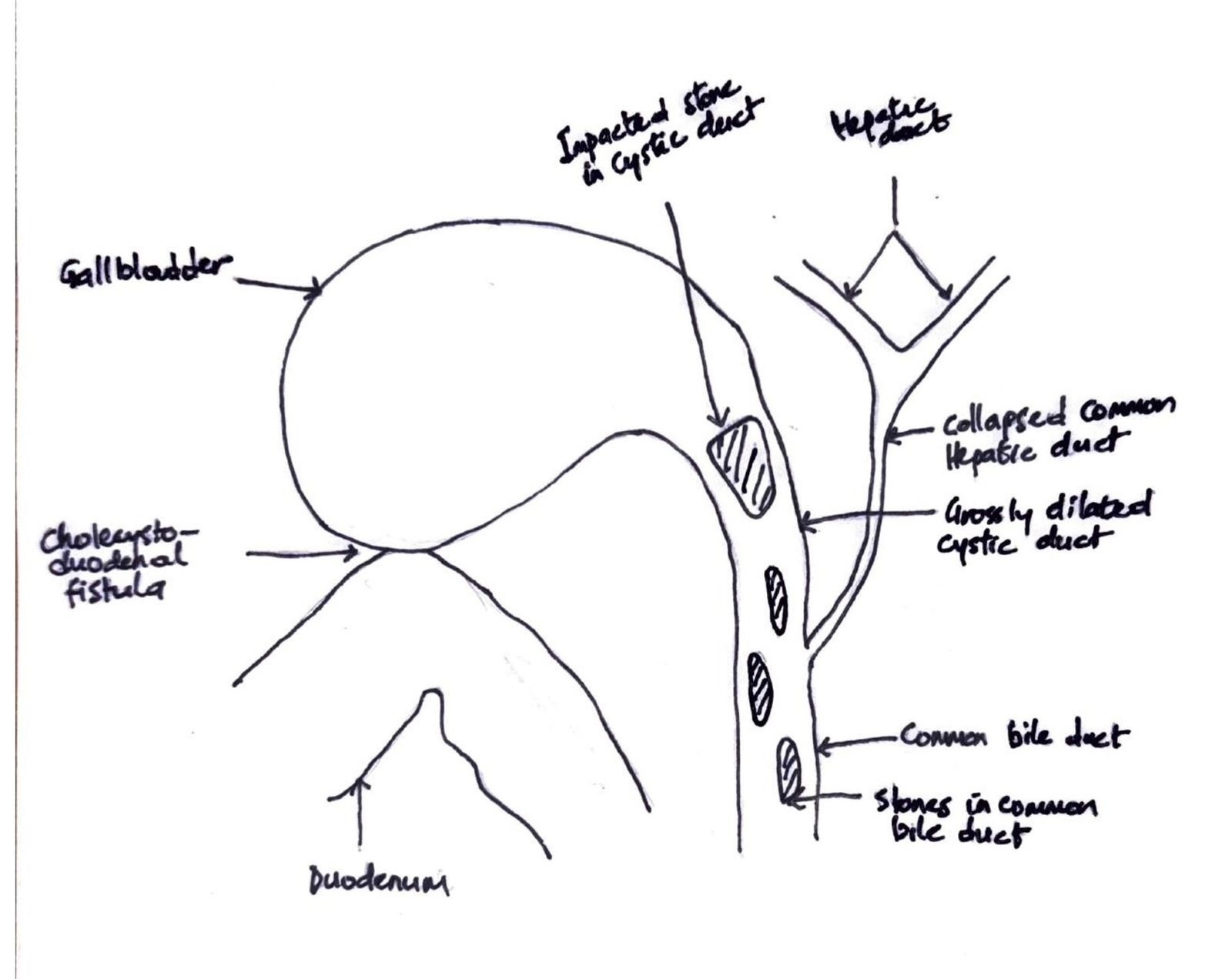

On examination, she was in fair general condition, afebrile and not icteric. The abdominal exam was normal. All relevant laboratory investigations were within normal ranges, and we proceeded with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Intraoperatively, we noted extensive adhesions involving the gallbladder, omentum, and bowel. The gallbladder was firmly adherent to the cystic plate, rendering the surgery difficult. This prompted the team to opt for a bailout subtotal cholecystectomy. After dividing the gall bladder at the neck, a cholecystoduodenal fistula (Figure 3) less than 5mm was noted along with some bile leaks in the surgical field, reducing visibility. This led to the conversion to an open procedure through a midline incision. The duodenum was primarily repaired and secured with a pedicled omental flap. In an attempt to clearly define the biliary tree anatomy, we decided to explore the CBD. We made a 2cm incision on the anterior aspect of the CBD, which revealed a patent plastic stent in situ and multiple stones. The cystic duct was grossly dilated and found to be in continuity with the CBD. It contained multiple impacted stones, the largest measuring approximately 3cm. All stones were successfully extracted. A bile leak was noted at the cystic stump and was repaired primarily. The CHD was almost collapsed. The presence of a cholecystoenteric (cholecystoduodenal) fistula in a context of MS without gallstone ileus made us classify this as a Type 5A according to Csendes classification (Figure 4). The CBD was then repaired primarily. Abdominal irrigation was done, and a drain was left in situ. Postoperative monitoring was negative for bile leaks. The patient improved clinically, with liver function test normalising and was discharged after 10 days. Clinic follow-ups were scheduled every 3 months. The patient remained asymptomatic and is currently doing well and improving.

Discussion

The prevalence of gallstones is 15% in the USA and about 17% in Africa according to studies, with a greater frequency in females.5 We present this case to highlight the complex nature of diagnosis and management of MS.

MS typically appears in older patients and in 70% of cases in females. Some documented risk factors are large gallstones, chronic cholecystitis and anatomical variations of the biliary tree with minimal insertion of the cystic duct, a tortuous cystic duct, a short cystic duct or a side-by-side cystic duct with CHD.3 In 18-25% of cases of MS, there is an anatomical variation of cystic duct.3,6 Some of the reasons why cholecystitis persists and eventually leads to MS include a reluctance to seek medical advice, the use of proton pump inhibitors to treat biliary colic, or a reluctance to accept the surgical recommendation of a cholecystectomy.7 Our patient had been symptomatic for years but because the pain was bearable, she did not seek medical attention. Symptoms of obstructive jaundice are usually late presentations of MS due to extrinsic CHD compression by gallstones.3 In elderly patients presenting with obstructive jaundice, common differential diagnoses include pancreatic carcinoma, gallbladder cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, and metastatic disease. However, MS should also be considered as a potential etiology.

The significance of this disease stems from the technical challenge of locating the cystic duct during a cholecystectomy, which increases the likelihood of bile duct injury (up to 17% in patients). Therefore, a preoperative diagnosis is crucial.3,6 While ultrasound has 90% diagnostic accuracy for gallstones, it falls to 29% for diagnosing MS. While ERCP, the gold standard for diagnosing MS, has a diagnostic accuracy of 55%–90%, CT and MRCP are both below 50%.8 MRCP has the advantage of identifying other causes of biliary obstruction; as such, it is the preferred diagnostic method for MS. However, most surgeons opt for dual imaging.3 According to these studies, the gallbladder’s dimensions can be used to forecast technical difficulty because of its shrunken look, which offers insight into its chronicity and fibrosis. If present, pneumobilia in the absence of prior biliary intervention suggests fistula formation. This information was obtained in our case and should have raised our suspicions for MS. Also, it further diminishes the likelihood of an underlying malignant process but does not rule it out completely. As an adjunct to primary care, ERCP is particularly beneficial for poor surgical candidates or for patients with acute cholangitis, in whom biliary decompression serves as a temporary measure prior to definitive surgery. ERCP was done in our case for stone retrieval and CBD stenting to relieve the obstruction. It however failed to diagnose MS, just like CT and MRCP were inconclusive. However, preoperative diagnosis of MS is achievable in 18%–62% of cases, with more than 50% being intraoperative diagnoses.4

While laparoscopic cholecystectomy is preferable for most gallbladder surgeries, in cases of MS the open approach is recommended. One study advised against laparoscopy, citing a 16% overall complication rate, a 41% conversion rate, and a 0.8% death risk for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the context of MS.3,9 The best course of action depends on a number of criteria, including the patient’s age, MS type, and comorbidities. Several factors can increase the complexity of surgery5,6:

-

A low index of suspicion and the rarity of the condition may result in a missed preoperative diagnosis.

-

Dense adhesions from chronic cholecystitis can distort normal anatomical landmarks.

-

The presence of cholecystobiliary or cholecystoenteric fistulas increases the risk of bile duct injury or hemorrhage during dissection of Calot’s triangle.

-

Impacted cystic duct stones are often inaccessible via endoscopic approaches.

-

Bile duct injuries are the most frequent and feared intraoperative complication.

When dissection in the hepatocystic triangle is found to be unsafe, subtotal cholecystectomy with removal of all stones and preservation of the infundibulum and cystic duct is the standard “bail out” option.10 Because the diagnosis was not conclusive and we thought it was a routine completion cholecystectomy, the laparoscopic approach was chosen but we eventually converted, when it became obvious it was a type V MS. A type V MS is best managed by laparotomy with partial cholecystectomy and fistula repair.4

Bile duct injuries are the most frequent and feared intraoperative complication. They are repaired using techniques ranging from primary end-to-end anastomosis over a T-tube to more complex biliary-enteric reconstructions, such as Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, depending on the injury’s severity and location. The choice of technique is influenced by the timing of diagnosis (intraoperative vs. delayed), the extent and classification of the injury (Strasberg classification), and the presence of associated vascular or biliary tissue loss. Early recognition, minimal tissue tension, and the use of magnification with fine suture material are critical to optimize long-term outcomes.11

Surgeons should always entertain the possibility of occult gallbladder cancer in cases of MS, as both conditions are believed to be caused by chronic inflammation. Some studies report 5%–28% of gallbladder cancer in patients with MS post cholecystectomy according to pathology reports.1,12

A major limitation in this case was the many facilities involved in the care of the patient and the inadequate information available following each step of management. The lack of proper description of the findings and actions undertaken during ERCP made it hard to anticipate the level of difficulties encountered intraoperatively. Also, it would have been helpful to repeat imaging prior to the surgery, but this was not done.

Conclusion

Preoperative diagnosis, though crucial for avoiding complications associated with a cholecystoenteric fistula, remains challenging—even with the increased use of ERCP. Combining multiple imaging modalities is recommended to ensure optimal management. Clinicians should therefore maintain a high index of suspicion for this condition.

Ethical Approval

The study was determined to be exempt from ethical approval by the IRB per institutional guidelines.

Informed Consent

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of this case study. The journal’s editor-in-chief could assess a copy of the written consent on request.

Data Availability

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Funding

Regarding the intent of conducting research, writing, and/or publishing this paper, the writers did not receive any funding or grants.