Introduction

Pain is characterized as an unpleasant sensory and emotional encounter arising from real or potential tissue injury.1 Orthopedic surgery involves significant muscle and skeletal tissue repair or reconstruction, which leads to severe pain.2 Various factors, such as preexisting pain, anxiety, youth, and the nature of the procedure, have been identified as potential contributors to postoperative pain.3–5 A recent extensive study performed by Ndebea et al in Tanzania revealed a direct correlation between intense postsurgical pain and subsequent complications, such as an increased risk of thromboembolic events, delays in ambulation or rehabilitation, and respiratory impairment. Therefore, there is a critical need for effective pain management.6

Orthopedic and trauma postoperative pain presents a number of challenges to attending health workers, not the least of which is the offering of safe and effective postoperative pain management.2 Postoperative pain management remains a major challenge for many surgeons, nursing teams, and anesthesiologists, especially in low- and middle-income countries.6,7 This problem is further compounded by the shortage of staff, specifically nurses, at the frontline of health service delivery.7,8 The challenge is exacerbated by the increase in road traffic accidents in low- and middle-income countries.9

Despite the increase in orthopedic and trauma cases and the shortage of staff in this group of patients, effective control of postoperative pain is vital for improving patient outcomes. We conducted this study to assess pain care in a low-income country setting, which, to the best of our knowledge, is the first study in the country.

Research Methods and Design

This was a cross-sectional study carried out at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre Malawi, which serves a total population of 7,750,629 in the southern region. Approximately 15 patients with long bones are operated on each week. In this study, long bone fractures included humerus, tibia, fibula, radius ulnar, and femur fractures. This population was chosen because common injuries and complex procedures create a need for adequate pain management to prevent pain-related complications.

Even though the radius and ulnar are functionally not long bones, they were included from an anatomical standpoint. The inclusion criteria included all patients who were 18 years or old who underwent surgery on a long bone fracture. Patients who did not undergo surgery for long bone fractures, pediatric patients, individuals whose pain levels or experience were not reliably communicated, patients with cognitive function impairment, and patients who could not receive standard pain medications due to allergies or other health conditions were not included.

Every patient who met the inclusion criteria and signed an informed consent was recruited within 48 hours post-surgery. Data were collected via a questionnaire to the participants, which covered demographics, date and type of procedure, procedure duration, type of anesthesia used, type of analgesics prescribed and administered, type of adjunct pain management (e.g. nerve block, infiltration of the incision, epidural), interval between the surgery and first dose of analgesics, and level of pain satisfaction. Surgery duration was measured from the end of the time-out process on the World Health Organization (WHO) checklist to the moment the patient was ready for transfer to recovery.

Pain levels were assessed using the numeric pain scale (0–10). In addition, patients indicated whether their reported pain level reflected satisfaction with the analgesia administered, neutrality, or dissatisfaction.

The data were captured in Microsoft Excel, sorted, and then transferred to IBM SPSS Statistics. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the cohort characteristics, presented as frequencies with percentages for categorical variables and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. Patient satisfaction was analyzed as a categorical variable. The association between protocol adherence and satisfaction, as well as the effect of spinal anesthesia (using a 7-hour analgesic window), was assessed using a χ² test. The relationship between prolonged surgical time and satisfaction was analyzed with a χ² test. The influence of age on postoperative pain was evaluated using logistic regression, with results reported as an odds ratio (OR) and confidence interval. The association between surgical invasiveness and postoperative pain was tested using Kendall’s Tau-b rank correlation. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

A total of 66 patients were interviewed between April and May 2025. Although the study initially aimed to recruit 150 patients within the study period, delays in obtaining final institutional approval and constraints related to the academic timeline limited enrolment to 66 participants. Additionally, some of the projected 150 patients were pediatric cases and therefore excluded from the study. The cohort comprised 55 males (83.3%) and 11 females (16.7%), with a median age of 39 years (IQR: 26.8–49.3), as shown in Table 1.

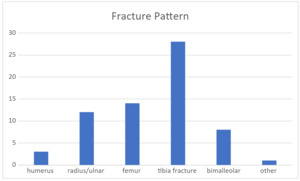

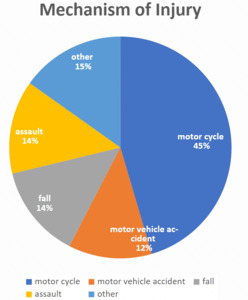

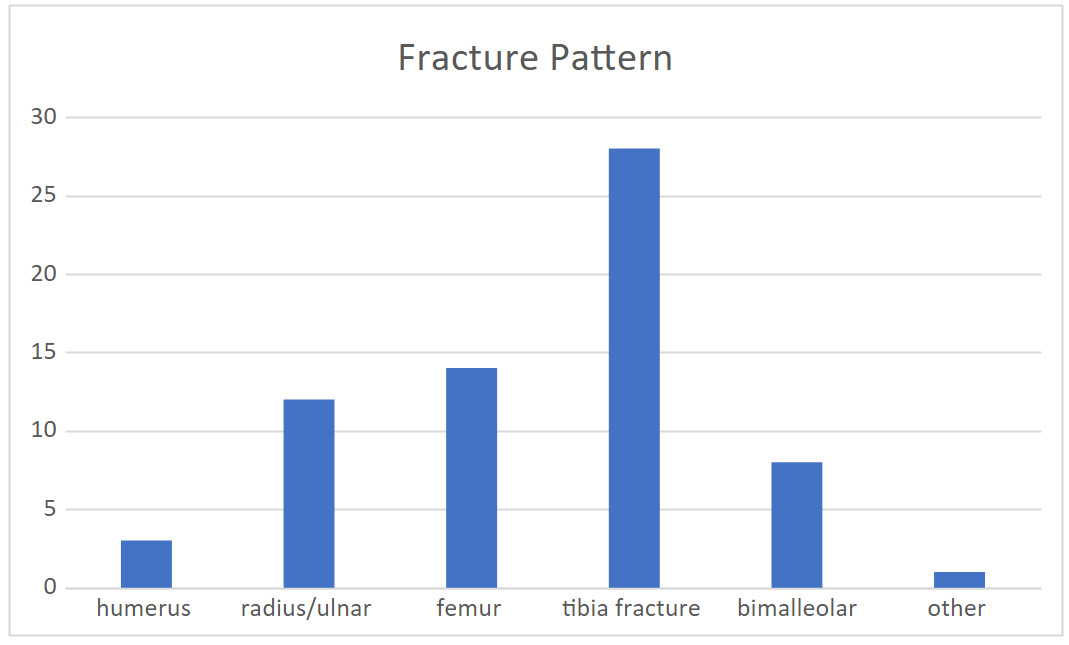

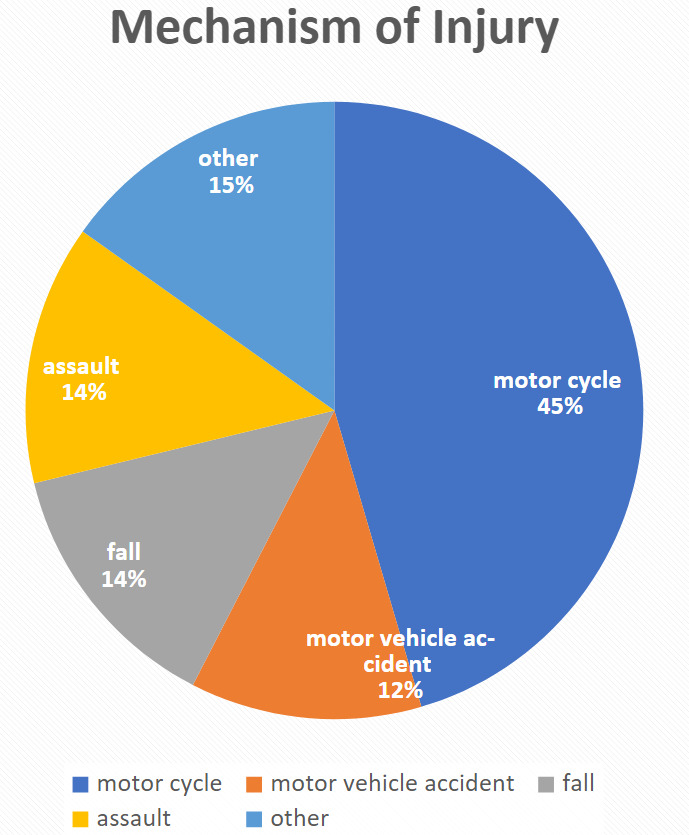

The most common fracture types were tibia and fibular (42%, n = 28) and femur fractures (21%, n = 14). The significant mechanism of injury was road traffic accidents (60.6%, n=40), with motorcycle-related injuries (45%, n = 30) being the most common. In total, 92.4% of participants were satisfied with the pain management despite not being administered pethidine according to prescription. The results on type of fracture and mechanism of injuries are summarized in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Most patients were operated under spinal anesthesia (49.1%, n = 39) and some (40.9%) under general anesthesia. There were no regional blocks for upper limb procedures (see Table 1). Drugs prescribed post-surgery were pethidine, ibuprofen, and paracetamol. All were indicated to be in stock but even then, were given invariably.

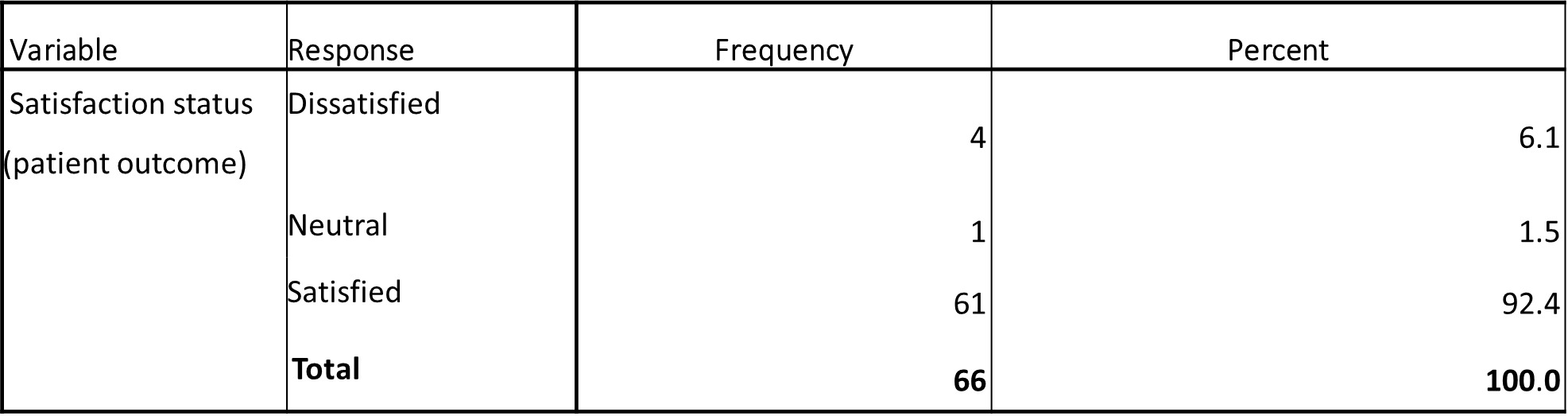

The proportion of satisfied patients (92.4%, n = 61) was significantly greater than the proportion of neutral (1.5%, n = 1) or dissatisfied (6.1%, n = 4) patients, as shown in Table 3. This finding strongly indicates that the overall patient experience with pain management was overwhelmingly positive. However, the study did have methodological limitations. Of note, patients were not assessed for their preoperative pain levels for comparison with their postoperative pain levels or pain control satisfaction.

Analysis revealed no statistically significant associations between whether a patient received the analgesic regimen as requested or prescribed and their reported satisfaction level (P = 1.000). Pain vs analgesia delay (P = .070) showed a strong, marginally significant trend. Longer waiting times for pain medication was associated with higher pain scores.

Given that 39 patients underwent surgery with spinal anesthesia—which may have residual analgesic effects postoperatively, potentially confounding satisfaction rates—we implemented a 7-hour threshold for analgesic administration. Patients receiving their first analgesic dose ≥7 hours post-surgery were classified as outside the analgesic window; those receiving it within 7 hours were classified as under residual anesthetic effect. The χ² = 0.035 and P = .85. Satisfaction levels were consistently high in either group, irrespective of first analgesic timing. The association between prolonged surgical time (>2 hours) and patient satisfaction was assessed. A χ² test of independence revealed no statistically significant associations between the 2 variables (χ² (1) = 0.54, P = .461).

Younger age was not a significant predictor of higher postoperative pain levels (OR: 0.987, P = .398). Education level did not show significant differences in pain scores, albeit a majority of the participants were primary school level (see Table 2). Kendall’s Tau-b analysis revealed no significant monotonic association between surgical invasiveness (in this case defined by prolonged duration of surgery, >2 hours of average theatre time) and postoperative pain levels (τb = 0.114, P = .217).

Discussion

This study investigated pain management after orthopedic and trauma surgery and reported that pain was inadequately managed. This study highlights the compelling insight into the complex nature of postoperative pain management in resource-restrained trauma and orthopedic settings. This was evidenced by the satisfaction paradox, with 92% reporting satisfaction when there was very low adherence to the postoperative pain control protocol.

Postoperative analgesia in our cohort was achieved using pethidine, ibuprofen, and paracetamol, all of which were available within our setting, although administration varied among patients. Pethidine was selected as the primary opioid agent in place of morphine, largely due to the prevailing perception that it is “safer” with respect to respiratory complications. Alternative agents such as oxycodone or combination preparations like Percocet were not accessible in our practice environment, thereby limiting the spectrum of opioid choices. Adjunctive analgesic modalities—including incisional infiltration by the anesthetist, regional techniques such as nerve blocks or epidural analgesia, and nonpharmacological measures such as cold compress application—were not employed in this cohort. Pain management, therefore, relied exclusively on systemic pharmacological agents, reflecting both the resource constraints and the prevailing clinical practice patterns in our setting. This regimen does not align with the principles of multimodal analgesia, which are strongly supported by current evidence. Multimodal strategies emphasize preemptive analgesia, such as incisional infiltration by the anesthetist, alongside nonpharmacological measures, including limb elevation and cold therapy, as well as regional techniques like epidural analgesia.10–12

The absence of a statistically significant association between postoperative pain and patient satisfaction (P = 1.000) was counterintuitive. In developed countries, such a marked deviation from postoperative pain control, particularly the skipping or omission of opioids such as pethidine, typically strongly correlates with poor pain control and low patient satisfaction.2,5 Our findings suggest that outcomes may be influenced by socioeconomic and educational background. With high rates of injuries from motorbike accidents (45%), a marker of a predominantly young working-class male population, it is likely that many patients have limited education 65% (n = 43), having attended only primary school education. This may translate to a lack of awareness of their right to health in general and their right to effective pain relief. In other African contexts, trauma patients accept pain as an inevitable result of injury and surgery and may not feel empowered to demand the required pain treatment.6,7 Patient satisfaction may reflect gratitude for the life- or limb-saving surgery itself rather than a critical provision of postoperative comfort from pain. On the other hand, the satisfaction paradox in this case may be due to the free health care model. Patients’ expectations are calibrated differently if they do not pay for the service they are receiving. They gravitate toward accepting whatever is provided without complaint, viewing it as a benefit rather than guaranteed right. This shapes a low benchmark for satisfaction, where mere administration of some analgesia, even if it is suboptimal or delayed, is deemed acceptable. In our cohort, patients were in a hospital where they do not offer paying services, which did not allow us to test this hypothesis.

The view of this being a free service center and the predominance of road traffic injuries, particularly those involving motorcycles (45%), is consistent with regional data from Malawi and neighboring countries.9 This epidemiological burden imposes constrained demands on an already overwhelmed health care infrastructure. Staff shortages contribute to burnout and may result in lapses in protocol adherence, including missed analgesic doses. Additionally, the limited availability of medications and equipment fosters a climate of scarcity, wherein analgesics may be rationed or reserved for the most severe cases. These constraints directly contribute to the nonadherence observed in this study and render consistent, protocol-driven care exceedingly difficult to maintain.

Our analysis revealed no significant association between the level of surgical invasiveness and postoperative pain level (τb = 0.114, P = .217). This differs from the findings of other studies in developed settings, where more invasive surgical procedures (e.g., intramedullary nailing, open reduction and plating) are consistently linked to higher pain scores.3,13 This disparity may be attributed to the overwhelming mechanism of injury in our study population: high-energy road traffic accidents (57%). The significant preoperative pain and psychological trauma from such events may create a ceiling effect, where the additional pain from surgery, regardless of its invasiveness, is not perceived as markedly different.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study, which limits its ability to capture long-term outcomes and track the causality of the findings noted. The small sample size of 66 participants from a single hospital greatly limits the statistical power and generalizability of the findings to other populations or settings. Furthermore, the patient population was overwhelmingly dominated by young males injured in road traffic accidents, which restricts the applicability of the results to female patients, elderly patients, or those with fractures from other mechanisms. The inability to use visual analogue scale scores or other standardized pain scores to compare effectiveness of the pain treatment undermined the overall impact. Also, the lack of institutional guidelines, multimodal or otherwise, resulted in individualized treatments and possibly contributed to lack of conformity to postoperative pain treatment requests.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In conclusion, the high satisfaction scores in this study should not be misinterpreted as excellence in pain management. Instead, they reveal a complex interplay of low patient expectations, cultural acceptance, and systemic constraints. By recognizing this paradox, health care providers can move beyond satisfaction scores as a sole metric and work toward implementing concrete, auditable standards of care that ensure not only patient satisfaction, but also genuine and effective postoperative pain relief for all.

To improve postoperative pain management, the study recommends implementing and enforcing clear, standardized protocols tailored to local resources and supported by regular clinical audits to monitor adherence and identify gaps. It further advocates for educating and empowering patients about their right to pain relief and fostering a collaborative relationship with staff. Finally, it calls for broader systemic advocacy, both for public health measures, such as improved road safety, and for increased internal hospital support to address critical staffing and resource shortages.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, the director, and the head of the surgery department for the approval of this study.

Ethical Approval

Permission to conduct this research was obtained from the College of Medicine Research Committee (Ref. P.08/24-0968) and the hospital director.

Informed Consent

All participants provided written, informed consent.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, VLM.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and were not influenced by any materials or financial interests in the development of these findings.

Funding

No funding was received while the study was carried out.