Introduction

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Rwanda, access to essential surgical care remains limited, particularly for pediatric patients.1 With nearly one-half of Africa’s population under the age of 18, the burden of untreated surgical conditions in children is a significant public health concern, as greater than 95% of individuals do not have access to safe and timely surgical care.2,3 In Rwanda, the need for pediatric surgery is compounded by the scarcity of specialists; there are 3 pediatric surgeons for nearly 5 million children, compared with approximately 3 pediatric surgeons for every 150,000 children in the United States.4,5 Rwanda emphasizes a decentralized health care model within a universal health insurance program and network to increase access to care at the population level. In this model, children with surgical conditions are often first evaluated at first-level (district) or second-level (regional) hospitals, many of which are located rurally. For pediatric surgical conditions, district and regional hospitals focus on diagnosis, resuscitation, and referral to higher levels of care, although some regional hospitals may also have capacity for emergency and elective pediatric surgical care.6 Specialist pediatric surgical services are only available at third-level referral hospitals in the capital of Kigali. Therefore, children presenting to a district or regional hospital are evaluated and managed by general practitioners (GPs); in this context, medical doctors with no specialist residency training) and medical interns prior to definitive transfer.

Current training for GPs in Rwanda does not sufficiently address pediatric surgical care, particularly in remote areas where most surgical emergencies are initially evaluated.7 About 90% of essential pediatric surgical procedures appropriate for district hospitals, as determined by an expert Delphi, are currently not available at 3 major district and regional hospitals in rural Rwanda.8 In addition, GPs have limited training in the basic diagnosis, stabilization, and transfer of children with surgical needs, leading to delays in care. Previous efforts have shown that timely transfer to tertiary centers with pediatric surgical expertise can drastically improve patient outcomes.9,10 However, it is unknown what care is provided to children with surgical conditions at rural hospitals by GPs, especially as the capacity to provide advanced subspecialty care in pediatric and neonatal surgery improves in Rwanda.

We therefore aimed to understand the practice patterns and knowledge gaps of GPs in Rwanda regarding the initial management of pediatric surgical conditions. We surveyed GPs and medical interns (doctors in their first year of practice) at 5 district and regional hospitals in rural Rwanda, identifying key aspects of their background, attitudes, and knowledge related to the diagnosis, stabilization, and transfer of children with surgical conditions. We hypothesized that there exist significant gaps in knowledge, which can be areas for targeted education to improve early pediatric surgical care.

Methods

Needs assessment development

A two-stage modified Delphi process involving Rwandan pediatric surgeons and anesthesiologists was performed to develop a needs assessment evaluating GP knowledge on burden of neonatal surgical conditions, perceived outcomes, understanding of initial management, and transfer criteria and transfer timing for priority neonatal conditions. A separate two-stage modified Delphi process involving international and Rwandan experts in pediatric surgery, anesthesia, and critical care was conducted to identify a list of pediatric surgical conditions in Rwanda to be prioritized.11 Notably, GPs who had lived experience in rural district hospitals were involved in creating this consensus. We utilized the results of these 2 Delphi processes to guide the development of a needs assessment focused on 9 prioritized neonatal and pediatric conditions (Supplementary Table 1). The needs assessment evaluated participants’ ability to diagnose, initially manage, and perform timely transfer of children with these conditions to a tertiary hospital with pediatric surgical services. Correct answers were confirmed by the senior author, a Rwandan pediatric surgeon. The needs assessment also assessed participants’ demographics and training backgrounds. The needs assessment was refined using cognitive interviewing with Rwandan GPs and surgical trainees. IRB approval was obtained from the Rwanda National Ethics Committee (No.504/RNEC/2024) and the University of Michigan (HUM00270496).

Sample size calculation

We calculated the number of participants needed to adequately sample the approximately 1200 GPs in Rwanda using the calculation n’ = n / (1 + (z² × p̂ × (1 - p̂)) / (ε² × N)), where z is the z score; ε is the margin of error; N is the population size; and p̂ is the population proportion. For the population proportion, we used p̂ = 0.5, which provides the most conservative (largest) sample size when the true proportion is unknown. Given that Rwanda has approximately 1200 GPs, for sufficient study power for finite population sampling, at least 89 GPs were needed for a confidence interval of 95% with 10% margin of error.

Distribution, participants, analyses

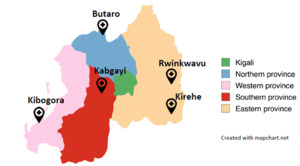

Sites were enrolled on a rolling basis to achieve the calculated necessary sample size. Five district and regional hospitals spanning the geography of rural Rwanda, selected by convenience sampling, participated as survey sites (Figure 1). All GPs (medical doctors with no specialist residency training) and medical interns (doctors in their first year of practice) at these 5 sites were invited by their hospital director general to complete the survey via REDCap. Surgical residents in their first week of training at Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Kigali (CHUK) who were GPs just prior to starting were also invited to take the survey to meet sample size requirements. A total of 105 physicians were invited to participate. The survey link was distributed via WhatsApp, and to avoid bias against individuals with limited WhatsApp access, study team members were also present at the hospitals to request completion of the survey at times during which GPs and interns did not have patient care duties. Chi-square tests were performed to determine whether demographic variables impacted knowledge. Analyses were performed using RStudio v1.1.4.

Results

Demographics and experience with common conditions

Ninety-two participants with heterogeneous experience (out of 105 invited, 88% response rate) completed the needs assessment (Table 1). Most GPs (80.7%) had worked at another hospital within Rwanda, and 11.5% had worked at another hospital outside of Rwanda. Some participants (41.3%) had completed a pediatric surgery rotation in medical school, and most felt that it was useful. All participants saw children with surgical needs, either rarely or often.

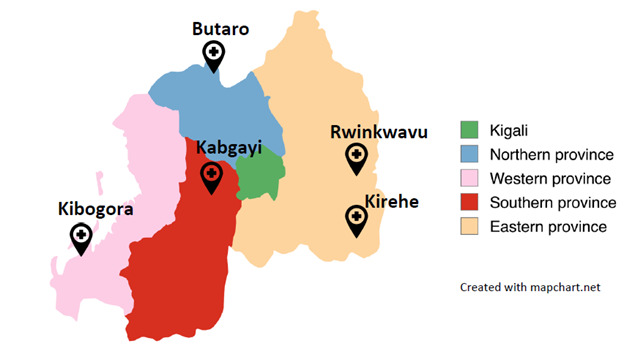

Most transfers occurred due to need for specialist management; lack of equipment and knowledge were also cited as reasons for transfer (Figure 2A). Common barriers to transfer included unavailability of beds at referral hospitals and cost (Figure 2B).

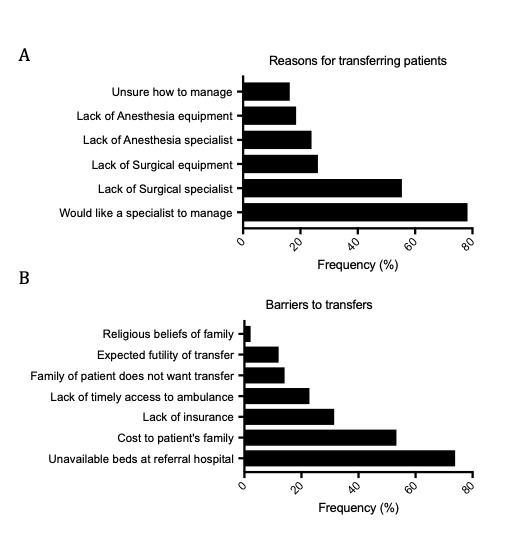

Among the 9 conditions examined in the needs assessment, the most commonly seen conditions in children were inguinal hernia and undescended testes; gastroschisis was the third most commonly seen condition (Figure 3A). Intestinal atresia and anorectal malformation were the least commonly seen, with 29.3% and 38.1% of participants reporting seeing these conditions at least once per year. Challenges in specific knowledge about common conditions were cited by 63%–84% of participants (Figure 3B). Materials and patient factors were also identified as challenges in care. Depending on the condition, 18%–65% of participants reported having seen patients with the studied conditions in follow-up after having transferred them to a tertiary care center.

Diagnosis, initial management, and transfer

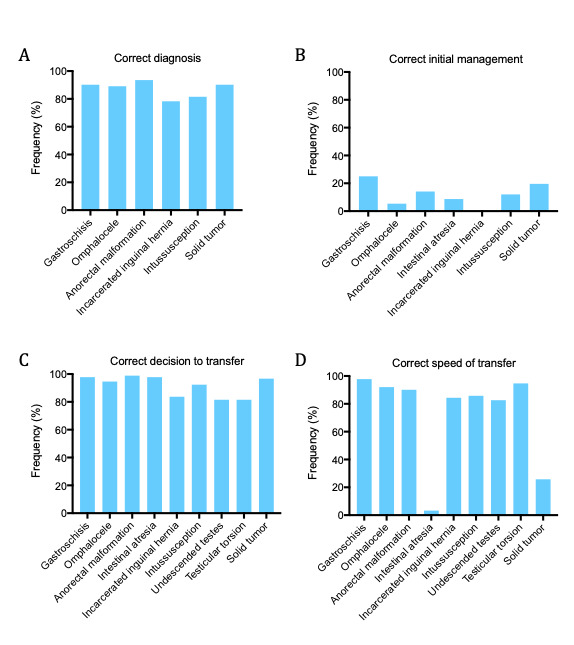

The conditions were correctly diagnosed by 78%–94% of participants (Figure 4A). Forty-two participants (45.7%) incorrectly diagnosed at least one condition.

Correct initial management of the conditions was variable. Participants correctly identified appropriate use of IV fluids and PO antibiotics; however, fewer participants correctly identified appropriate use of IV antibiotics, orogastric tube decompression, and management choices specific to individual diagnoses (ie, sterile coverings for gastroschisis; see Supplementary Figure 1). Few participants (0%–25%) correctly answered all questions assessing the accuracy of initial management (Figure 4B).

Most participants reported that they would transfer their patients for pediatric surgical care (Figure 4C). A minority of participants indicated that their hospital’s general surgery team could provide definitive treatment for select conditions. Fewer participants indicated an appropriate transfer speed, especially for the 2 conditions with less urgency to transfer (intestinal atresia and solid tumor; see Figure 4D).

Differences between groups

We examined whether demographic factors affected participants’ knowledge about the aforementioned conditions. When comparing differences between the 5 hospitals, we found that participants from one hospital, which had robust general surgical services, were less likely to transfer patients with testicular torsion to tertiary care (46.7% indicating they would transfer, compared with 66.7%–100% at the other hospitals, P = .02; Figure 5A). These participants reported that their general surgery team often managed these cases independently. Otherwise, there were no significant differences in knowledge about initial management between hospitals.

When comparing differences between GPs and interns, we found that only 27.5% of interns had completed a pediatric surgery rotation, compared to 51.9% of GPs. Interns were less likely to have seen a child with an inguinal hernia (62.5% vs 86.5%, P = .007) and less likely to attempt bedside hernia reduction (32.5% vs 65.5%, P = .002; Figure 5B). Conversely, interns were more likely to have seen a child with intussusception (70% vs 57.7%, P = .03), and were more likely to correctly identify it on the knowledge assessment (92.5% vs 73.1%, P = .02). There were otherwise no significant differences in knowledge between GPs and interns.

Compared to participants who rarely saw pediatric surgical conditions, participants who often saw pediatric surgical conditions were more likely to be “confident” or “very confident” in their management (82.6% vs 54.3%, P = .004). Participants who often saw pediatric surgical conditions all correctly answered that neonates with gastroschisis should receive a sterile covering (100% vs 91.3%, P = .04) and were more likely to know what type of sterile covering to use (52.2% vs 26.1%, P = .01; Figure 5C). There were otherwise no significant differences in knowledge between those who often and rarely saw pediatric surgical conditions.

Discussion

In this study, we surveyed GPs and medical interns in Rwanda about their experience caring for children with surgical conditions and assessed knowledge gaps in the diagnosis, initial management, and transfer of these patients. Although responses diagnosing the selected conditions were mostly accurate, 45.7% of participants misdiagnosed at least one condition. Participants also had challenges identifying the appropriate initial management and timing surrounding transfer of patients to definitive care. These gaps in knowledge were largely consistent across hospitals, level of training, and experience seeing children with surgical conditions, with differences limited to one or two specific conditions.

Previous work has demonstrated that the majority of pediatric surgical procedures deemed appropriate for a district level hospital by an international expert consensus are not adequately available in Rwanda.6–8 Our study builds upon this work by assessing the initial management of pediatric surgical conditions prior to definitive transfer to tertiary care. We found that district and regional hospitals lack the necessary resources to provide adequate stabilization of certain pediatric surgical emergencies, including both human resources and essential equipment. Inadequate initial care at district and regional hospitals may lead to complications before patients reach referral hospitals. For example, in neonates with gastroschisis, poor hydration status and longer transfer time to a tertiary care center are both associated with increased mortality in an LMIC setting.12

Thus, there is a need for structured training in the management of pediatric surgical conditions for GPs and medical interns, as shown by their variability in knowledge and management skills. Although the knowledge gaps in our study were mostly consistent, there were some differences in ability to manage 3 of the most commonly seen conditions: gastroschisis, intussusception, and inguinal hernia. These findings suggest that medical training and experience are not uniform, and further training to standardize the ability to care for these conditions at rural hospitals is essential. Implementing this education as an essential component of medical school through dedicated preclinical didactics and increased exposure to clinical pediatric surgery would allow all doctors to graduate with an improved baseline of knowledge. In support of this, in our survey, 97.3% of doctors who had a pediatric surgery rotation found that it was helpful. Although there are few pediatric surgeons in Rwanda, the pediatric surgery service at CHUK as well as at the Rwanda Military hospital hosted students regularly and has been well received, allowing exposure to a large number of students. Additionally, interns, who were more recently in medical school, were more likely to correctly diagnose intussusception than GPs; this suggests that refresher trainings for GPs could be particularly effective. Previous work has shown that pediatric surgery-focused trainings in LMICs can be an effective way to build capacity among physicians.13–17 Our study expands upon this knowledge to suggest that targeted training to improve initial management at the GP level may be particularly useful. The educational needs include both knowledge-based and procedural-based training (ie, manual reduction of an inguinal hernia), pointing to the utility of a comprehensive course focused solely on the care provided at the rural hospital prior to transfer. As very few participants correctly answered questions about initial management, deliberately focusing on management techniques including appropriate antibiotic use, orogastric tube decompression, and disease-specific interventions such as sterile coverings is critical. Implementation of standardized management protocols for common pediatric surgical emergencies can also help GPs and medical interns make informed decisions. Thus, at the conclusion of the aforementioned study, we implemented a short course to address these needs, described in the following reference.18 Overall, strengthening GP and medical intern knowledge in the initial management of pediatric surgical emergencies may improve survival and reduce long-term disability, and point us to implementation objectives of designing, delivering, and evaluating contextually targeted training.

Our findings also demonstrate the need for improved systems of pediatric surgical care. Participants identified that cost and lack of beds at referral hospitals were two of the greatest barriers to the definitive transfer of their patients. These issues are difficult to address through training at the GP level alone. Increased capacity for definitive care by a pediatric surgical team is critical. The Rwandan Ministry of Health has recognized this need across all specialties, and in response launched the 4x4 Reform, a wide-reaching strategy to quadruple the number of specialists in the country within 4 years (2023–2027).19 An increase in the number of pediatric surgical providers, including surgeons, anesthesiologists, and specialized nurses, would allow for improved surgical care availability at regional hospitals, whether as full-time staff or as frequently visiting staff, addressing issues of bed availability as well as transport-related costs. This improvement in the local availability of care would not only provide curative interventions to patients in rural areas, but also improve financial, emotional, and social well-being for the patient’s entire family by alleviating the cost-related stress of the referral process. The expansion of pediatric surgery would also require improved availability of essential surgical supplies, as well as the strengthening of referral networks to optimize usage of available beds. These changes will require both significant time and significant funding; thus, short term solutions also include exploring the role of telemedicine and remote consultation to provide real-time pediatric surgical guidance to GPs in rural hospitals. In addition, as we found that one hospital was less likely to refer pediatric testicular torsion due because it was routinely managed by their general surgical team, implementing efforts to improve the ability and availability of general surgeons to manage scope-appropriate pediatric surgical conditions through pediatric surgical rotations and dedicated trainings could improve the availability of care.

Our study had several limitations. One limitation was that it focused only on 9 conditions, scratching only the surface of the breadth of pediatric surgical emergencies. However, these 9 conditions were based on a consensus by Rwandan and international experts, including GPs with lived experience in rural district hospitals, and thus represent some of the most important conditions managed initially at rural hospitals prior to definitive transfer. Another limitation was that it was conducted at a limited number of hospitals, which may not fully represent all hospitals in Rwanda. However, the hospitals spanned the geography of rural Rwanda, with at least one hospital surveyed in each of 4 rural provinces. The relative similarity of responses from each hospital may suggest that the responses are generalizable to other hospitals as well. Third, the ability to answer multiple-choice questions may not reflect actual clinical competence. For example, our survey’s classification of “appropriate” transfer urgency may oversimplify real-world diagnostic uncertainty, particularly for less urgent conditions like intestinal atresia, which may not be diagnosed until a child reaches the referral facility, and which may warrant immediate transfer given concern for volvulus. However, our questions focused on the key management decisions surrounding these conditions, thus representing a foundation of knowledge necessary for application into clinical care. Because English is a second or third language for most doctors, the delivery of the survey in English may also have limited their ability to fully demonstrate their medical knowledge. Finally, the care of children with surgical conditions requires not only GPs and pediatric surgeons, but also nurses, midwives, anesthesiologists, and general surgeons at district hospitals without pediatric surgeons. Accordingly, an important component of future work would involve expanding our scope to include other members of the care team.

Conclusion

GPs and interns recognize the importance of transfer of children with surgical conditions, but face challenges with knowledge, costs to the patient, and availability of specialty care. As pediatric surgical capacity improves, timely and safe transfer is critical to improve outcomes. Knowledge gaps exist in the diagnosis, stabilization, and transfer of children with surgical conditions among GPs in Rwanda, marking an opportunity for directed training with potential to improve patient care.

Ethical Approval

IRB approval was obtained from the Rwanda National Ethics Committee(No.504/RNEC/2024) and the University of Michigan (HUM00270496).

Informed Consent

All participants signed written consent forms approved by both institutions.

Data Availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

PJH was supported by NIH T32 CA009672 University of Michigan Surgical Oncology Research Training Program and the HBNU Fogarty Fellowship.

_participants_at_different_hospitals_(hos.png)

_participants_at_different_hospitals_(hos.png)