Introduction

Non-acute subdural hematoma (NASDH) is one of the most common intracranial hematomas and occurs predominantly in elderly individuals. These hematomas are characterized by a gradually enlarging collection of liquefied blood within the subdural space that exerts mass effect on the brain, resulting in neurologic impairment.1–3 Globally, the incidence of NASDH is estimated at 3.4–5 per 100,000 people in the general population and rises sharply to 60–80 per 100,000 among individuals aged ≥65 years with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 3:1. Despite this burden, there are only a few published Ethiopian studies and none come from Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (HUCSH), the largest and pioneering neurosurgical service center in southern Ethiopia.4–17

The understanding of NASDH pathophysiology has evolved from the earlier belief that it is caused primarily by a trauma-induced rupture of bridging veins. This mechanism alone does not adequately explain cases that follow minor or unrecognized trauma or the progressive nature of the hematoma. Current evidence supports a more complex process involving inflammatory cytokines, formation of fragile neovascular membranes, recurrent microhemorrhage, and continuous accumulation of blood within the subdural space.16,18–20 These mechanisms collectively contribute to hematoma expansion, fluctuating symptoms, and the risk of long-term neurological sequelae.

Clinically, a headache and focal motor weakness are the most common presenting symptoms. Most patients report a history of trauma—often minor falls among older adults—that aligns with findings from global studies identifying low-impact injuries as a leading mechanism for subdural bleeding.8,16,20,21 Radiologically, iso-dense hematomas are the most frequently observed, followed by hypo-dense types, and many patients show a significant midline shift or hematoma thickness greater than 2 cm. These patterns support existing evidence from low-resource settings where delayed presentation often results in larger hematoma volumes. Computed tomographic (CT) scanning remains the primary diagnostic tool across Africa, including Ethiopia, due to the limited availability of Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).8,9,13,22,23

Surgical intervention is indicated for symptomatic patients or those with significant brain parenchyma compression effects on imaging evidence. Burr-hole craniostomy with hematoma evacuation remains the mainstay of treatment worldwide. However, postoperative outcomes vary widely and are influenced by patient demographics, comorbidities, radiologic severity, perioperative management, and the quality of postoperative care. These factors may be particularly challenging in resource-limited environments where late presentation, limited neurosurgical capacity, and inconsistent follow-up can further affect neurologic recovery.

Given the limited prospective evidence from Ethiopia and the need for context-specific data to guide clinical practice in low-resource settings, this study was undertaken to assess the clinical profile and long-term neurologic outcomes of NASDH patients that were operated on at HUCSH to identify independent predictors of neurologic recovery and highlight opportunities for improving care at HUCSH in similar resource-constrained environments.

Methodology

This study was conducted at HUCSH, located in Hawassa City, Sidama Region, Ethiopia, approximately 273 km south of Addis Ababa, at coordinates 7°3′N and 38°28′E along the eastern shore of Lake Hawassa. HUCSH is a major teaching and referral institution that provides undergraduate and postgraduate medical education and delivers clinical services to an estimated 20 million people from Sidama, the former SNNPR, southern Oromia, the Somali Region, and even neighboring Somalia and Kenya. Since its establishment in 2003, the hospital has expanded to approximately 450 beds and now delivers emergency and specialty care to more than 102,000 patients annually. The neurosurgery unit, initiated in 2012 G.C with a single neurosurgeon, has now grown into a well-organized department unit staffed by 4 neurosurgeons and supported by numerous general surgery residents. It currently provides advanced procedures, including microscopic-assisted surgery and endovascular neurosurgical services, and continues to develop as a growing center for neurosurgical care, postgraduate training, and research.

The study was conducted from January 1, 2022 to December 31, 2024 G.C, using a prospective observational cohort design. This design was chosen to establish temporal relationships between preoperative risk factors and postoperative outcomes among patients with NASDH, an evaluation that cannot be adequately achieved through a cross-sectional approach. The source population included all patients diagnosed with NASDH during the study period, while the study population consisted of eligible patients who underwent surgical management and completed follow-up. Within the parameters of the study, we defined NASDH as a subdural hematoma that is non-clotted and no less than 3 days old, including subacute (presents between 4 and 21 days) and chronic (present for more than 3 weeks) subdural hematomas.

All surgically treated NASDH patients with complete medical records and 6 months of postoperative follow-up were included. Patients with incomplete medical records, those who did not undergo surgical intervention, or those lost during 6 months of follow-up were excluded. No patients were excluded based on frailty or preoperative risk. A census sampling approach was employed to maximize case inclusion. During the study period, 179 patients underwent burr-hole evacuation for NASDH; of these patients, 11 were lost during the 6-month follow-up and 7 had incomplete records. No deaths occurred during follow-up. A total of 161 patients met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis.

Data were collected by trained nurses, medical interns, and junior surgical residents using a structured checklist during admission and at 6-month follow-up assessments. Data were captured using Kobo Toolbox. To ensure data quality, the checklist was pretested in the same hospital setting, and each completed form was coded, checked for accuracy, and cleaned before entry. Data were then exported to SPSS version 26.3 for statistical analysis. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were used, and results were summarized according to key findings.

The primary outcome variable was the 6-month Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (Dead, Vegetative State, Severe Disability, Moderate Disability, or Good Recovery). Independent variables included patient age, comorbidities, mechanism of trauma, neurological symptoms, Glasgow Coma Scale score at admission, radiologic characteristics, intraoperative brain status, postoperative complications, subdural drain status, and length of hospital stay. Bivariable and multivariable binary logistic regression models were used to identify predictors of long-term neurological outcomes. For the purposes of outcome assessment, a favorable outcome was defined as a patient having postoperative upper and lower limits with good neurologic recovery at 6 months and an unfavorable outcome was defined as a patient having postoperative lower limits, moderate neurologic recovery, or worse at 6 months. The study was conducted after the institution review board approval letter was obtained from the HUCSH Department of Surgery Research Ethical Committee waiving individual consent with registration number Surg/377/2022. The data was extracted anonymously, and confidentiality was assured at each step of data collection and processing. The study complied with the principles of Helsinki and adhered to the guidelines provided for by STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology).

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of NASDH patients at HUCSH

The majority of patients were male (72.7%), with a median age of 60 years (IQR: 45–70). The oldest patient was 88 years old, and the youngest was 17 years old, with the age group of 60–79 years old accounting for the largest proportion (46%). The majority (76.4%) were from rural areas, mainly from the Sidama (52.8%), followed by the Oromia (33.5%) regions. Median symptom duration before presentation was 3 weeks (IQR: 2–3). While 82.6% had no comorbidity, Hypertension (7.5%) was the most common comorbidity identified (see Table 1).

Clinical characteristics of NASDH patients at HUCSH

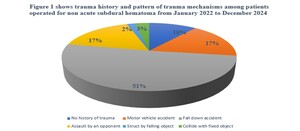

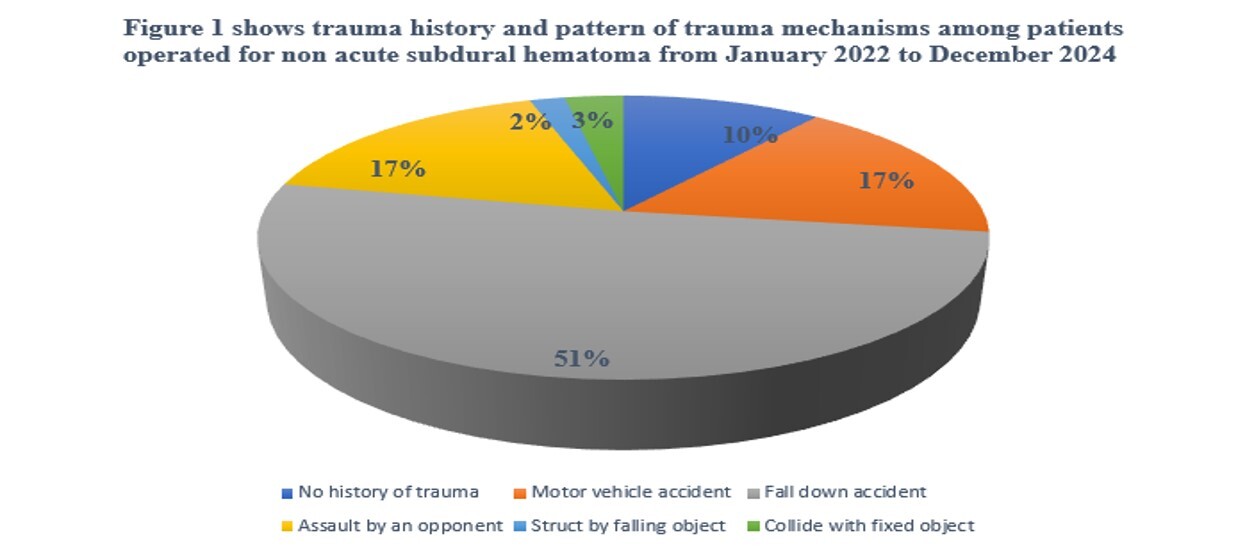

Headache (40.1%) and body weakness (33.3%) were the most common presenting symptoms. Older patients frequently presented with severe headaches and altered mentation, whereas younger individuals commonly exhibited variable body weakness and abnormal body movement. A trauma history was reported in 89.4% of cases, with most patients often suffering from simple falls (51%; Figure 1). In 81.4% of patients, the trauma occurred within 2 months prior to presentation. Most patients had an initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 15/15 (62.7%; see Table 2).

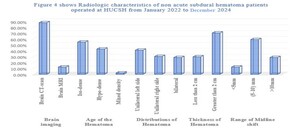

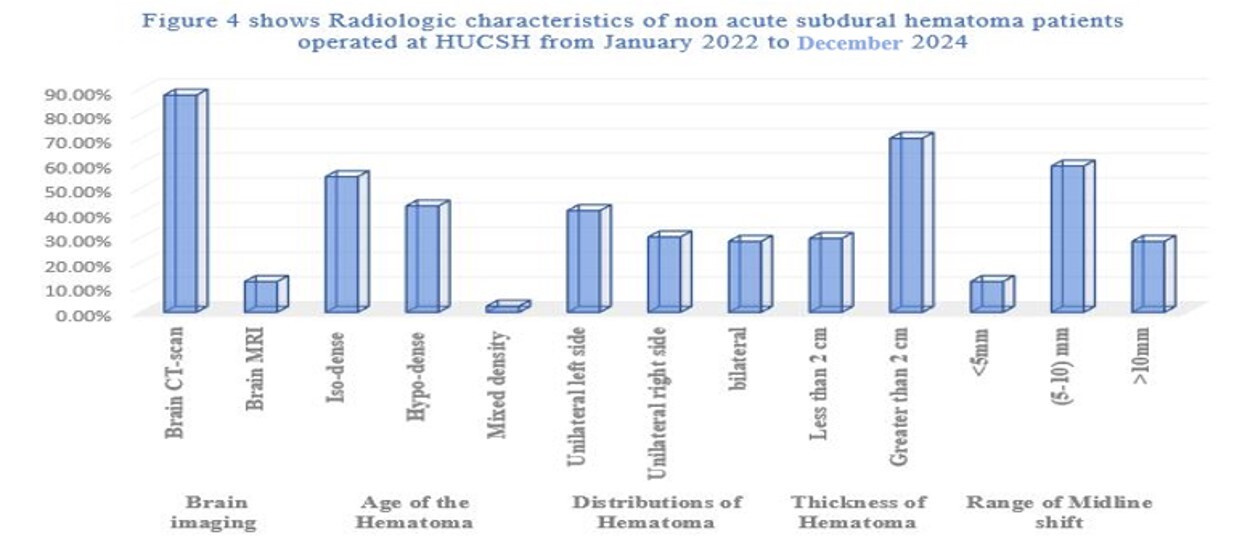

Radiological characteristics of NASDH patients at HUCSH

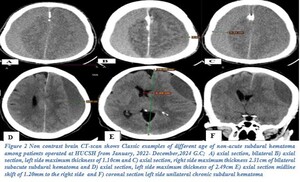

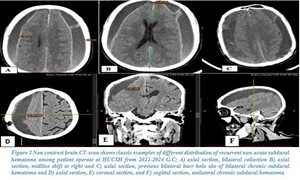

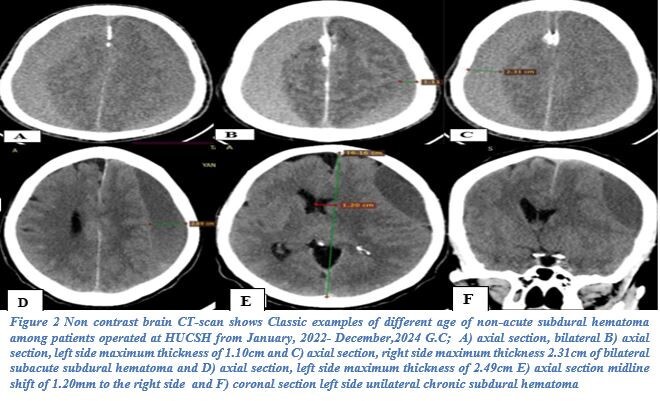

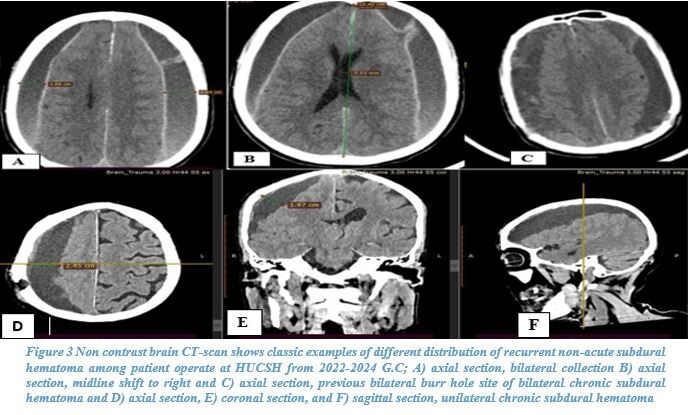

CT scan was the primary imaging modality used (87.6%). An iso-dense subdural hematoma was the most common radiological finding (54.7%), followed by a hypo-dense hematoma (42.9%). Most hematomas were unilateral (71.4%) with a left-sided predominance (41%). Most hematomas measured more than 2 cm in thickness (70.2%), and 59% demonstrated a midline shift of 5–10 mm (see Figures 2–4).

Intraoperative course of NASDH patients at HUCSH

All patients that were operated on received prophylactic antibiotics. Procedural sedation with local anesthesia was used in 97.5% of surgeries, most of which were performed by final-year general surgery residents under mentoring neurosurgeon supervision. Ipsilateral single-site burr-hole evacuation was the most performed procedure (72%), with the parietal bone being the preferred surgical site (96%). Most operations were completed within 60–90 minutes (74.5%), and intraoperative brain expansion was observed in 87.6% of patients (see Table 2).

Postoperative course of NASDH patients at HUCSH

Postoperative outcomes within 30 days were predominantly favorable with 81.4% of patients experiencing good outcomes. Flat head-of-bed positioning was routinely practiced. A drain was placed in all patients following burr-hole evacuation; however, drainage was managed using a locally modified nasogastric tube (French size 8) connected to a urine bag and secured with adhesive plaster in 100% of cases—an open, manually closed drainage system. Most patients (52.2%) required drainage for 24–36 hours, and accidental drain dislodgement occurred in 8.7% of patients and all of those patients were conservatively observed.

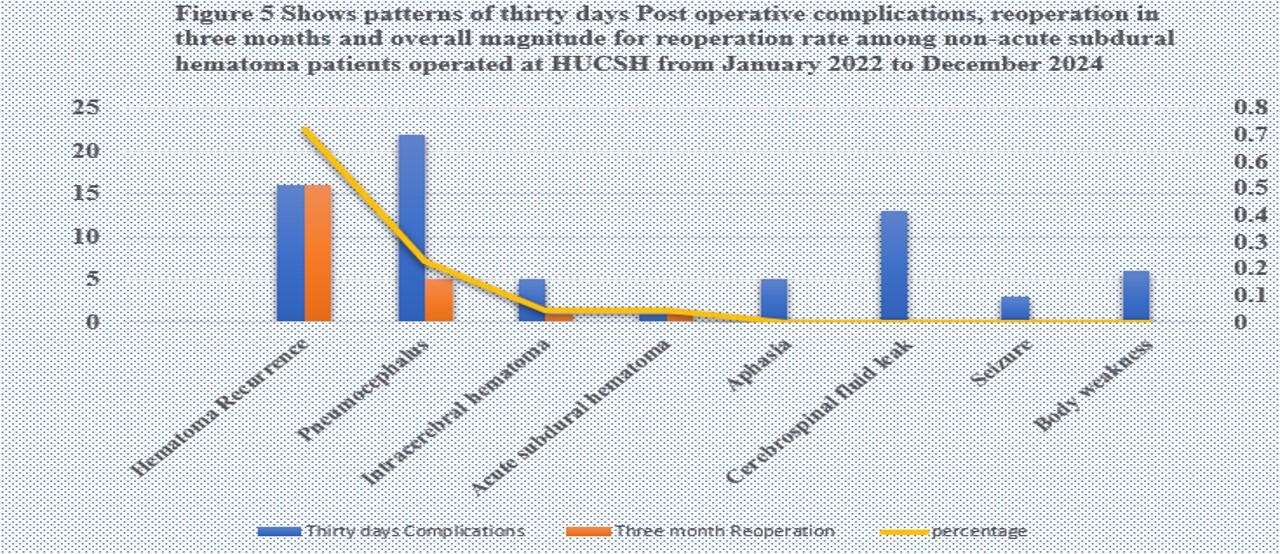

The most frequent postoperative complication was simple pneumocephalus (40%); however, only a few cases required reoperation. Cerebrospinal fluid leakage through the drainage site was noted in 23.6% of patients. Hematoma recurrence occurred in 9.9% (see Figure 5) with one patient experiencing three recurrences; this patient eventually underwent a craniotomy and evacuation, after which no recurrence was observed. Most recurrences (62.25%) were managed by widening the previous burr hole. Despite these complications, most patients (78.3%) had a short hospital stay of 1–3 days; no in-hospital mortality was recorded during the study period (see Table 2).

Bivariable regression analysis of NASDH at HUCSH

Bivariable analysis showed that several factors were significantly associated with long-term neurological outcomes. This included age, body weakness, GCS at admission, mechanism of trauma, comorbidity, postoperative complications requiring surgical intervention, and hematoma recurrence. Potential confounders identified included age, sex, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic alcohol use), medication history, hematoma size and laterality, etiology, time to surgery, preoperative GCS, surgical technique, drainage method, perioperative complications, and quality of postoperative care. These factors were controlled through strict inclusion criteria, standardized data collection, and multivariable logistic regression (see Table 3).

Multivariable regression analysis of NASDH at HUCSH

Multivariable logistic regression identified several independent predictors of outcome. Older age was strongly associated with poor outcomes with patients in higher age categories having 8.16 times greater odds of poor outcome compared to younger patients (adjusted odd ratio [AOR] = 8.158, 95% CI: 2.268–29.342, P = .001). The presence of body weakness at presentation was associated with significantly lower odds of favorable outcomes (AOR = 0.196, 95% CI: 0.044–0.866, P = .032). Higher GCS scores at admission were protective, with each unit increase reducing the odds of poor outcome by approximately 63% (AOR = 0.374, 95% CI: 0.166–0.839, P = .017). A midline shift was marginally associated with poorer outcomes (AOR = 2.97, 95% CI: 0.961–9.179, P = .05). Prolonged hospital stays were significantly associated with increased odds of poor outcomes (AOR = 5.044, 95% CI: 1.084–23.472, P = .039; see Table 3).

Discussion

NASDH has an estimated incidence of 1.7–20.6 per 100,000 people, predominantly affecting older adults and males. In our cohort, males accounted for 72.7% of patients, with a median age of 60 years (IQR: 45–70), and most cases occurred in the 60–79-year-old age group (46%). These findings are consistent with regional and global studies reporting male predominance and median ages around 63.3 ± 13.9 years.1,2,4,6,24–26 The higher prevalence in elderly males is often attributed to cerebral atrophy, increased susceptibility to minor head trauma, and comorbidities such as hypertension or anticoagulant use. Similar hospital-based cohorts in Addis Ababa and Gondar, Ethiopia, have reported comparable epidemiologic patterns. However, data on comorbidities, anticoagulant use, and rural versus urban residency are inconsistent across studies. In our cohort, most patients were from rural areas, and only a few subjects had comorbidities.3,5,7–17

Although our study did not examine the exact biochemical components of a NASDH, it is characterized by non-clotted blood and fluid accumulation in the subdural space. Current understanding attributes its pathophysiology to an inflammatory cascade that stimulates fragile capillary angiogenesis, progressive bleeding, and ongoing hematoma expansion. This contrasts with older theories that attributed NASDH solely to a trauma-induced rupture of bridging veins, which did not fully explain the occurrence of hematomas after minor trauma or their gradual accumulation.16,18–20 Clinically, the most common presentations in our cohort were headaches (40.1%) and body weakness (33.3%), consistent with global reports. Seizures and altered mentation were less frequent. Trauma history was reported in 89.4% of cases, primarily due to falls. Supporting literature identifies minor falls as a leading mechanism for NASDH in older adults. Interestingly, our observed trauma rate is higher than rates reported in Western cohorts.8,9,13,22,23

Radiologically, iso-dense hematomas were most common (54.7%), followed by hypo-dense hematomas (42.9%), with the majority showing a significant midline shift and thickness greater than 2 cm. These findings suggest delayed presentation, a common issue in low-resource settings, which result in larger hematoma volumes. The reliance on CT scans (87.6%) as the primary diagnostic tool is consistent with practices in most African neurosurgical centers due to limited MRI availability and prolonged scan times.8,9,13,22,23

Surgical intervention remains the mainstay of treatment for symptomatic or compressive NASDH. In our cohort, 96% (n = 155) underwent single-site parietal burr-hole evacuation. This approach aligns with evidence from systematic reviews, including studies in Brazil, that demonstrated comparable outcomes between single versus multiple burr-hole techniques or twist-drill craniostomy. In contrast, studies in Accra, Ghana, reported hematoma recurrence rates of 21% that were associated with bilaterality and hypertension—higher than our recurrence rate of 9.9% (n = 16), which showed no clear association with comorbidities or hematoma distribution. Globally, hematoma recurrence after burr-hole evacuation ranges from 0.36% to 33%.8,10,14,21,27 These findings confirm that burr-hole evacuation remains an effective and reliable surgical intervention for NASDH, even in resource-limited settings.

Postoperative outcomes in our study were generally favorable, with 81.4% achieving good long-term outcomes at 6 months. The most common complication was pneumocephalus (40%), which was higher than in some studies but manageable with conservative care. While craniotomy remains the last resort for recurrent NASDH in limited-resource settings, advanced techniques such as endoscopic middle meningeal artery embolization or membranectomy carry higher risk and require specialized infrastructure despite their effectiveness.11,28–30

Multivariable analysis identified older age, low GCS at admission, midline shift, body weakness at presentation, and prolonged hospital stay as independent predictors of a poor outcome. Older age likely reflects reduced neuroplasticity, higher comorbidity burden, and vulnerability to cerebral ischemia and systemic complications. Low GCS at admission indicates early neurological compromise, which indicates either primary brain injury or secondary mass effect from hematoma expansion. Midline shift represents significant mass effect, often resulting from larger hematomas or delayed presentation due to limited healthcare access or low awareness in rural communities. This mechanical compression can compromise cerebral perfusion, increase intracranial pressure, and predispose patients to long-term neurological deficits. A prolonged hospital stay may be a surrogate for early in-hospital complications, hematoma severity, or preexisting comorbidities, which can increase exposure to nosocomial risks, delay rehabilitation, and reflect the cumulative burden of disease and treatment. Body weakness at presentation likely indicates early neurological deficit or cerebral injury, leading to slower recovery and functional impairment. Although these associations are supported by prior studies, their exact mechanistic contribution requires confirmation through multicenter prospective studies. Contrary to some high-income country data, gender and comorbidities such as hypertension or diabetes were not independently associated with outcomes in our cohort.5,11,18,19,21,28–31

This study provides critical insight into NASDH management in resource-limited settings. By identifying key predictors of poor outcome, including older age, low GCS, midline shift, body weakness, and prolonged hospital stay, the study highlights the importance of early recognition, timely intervention, and close monitoring of high-risk patients. Moreover, it contributes valuable epidemiologic, clinical, and outcome data for NASDH in Ethiopia, addressing a significant gap in the regional neurosurgical literature and providing a foundation for future multicenter studies.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations. First, some data were prospectively collected from manually recorded patient charts, which introduced challenges related to legibility, completeness, and accuracy. Poor handwriting and inconsistent documentation occasionally affected the reliability of data during collection and follow-up. In our setting, where paper-based records are still standard, these limitations were unavoidable. Second, some important clinical variables, such as duration of anticoagulation or steroid use, presence of a subdural membrane, and management of incidentally dislodged drains, were inconsistently recorded or entirely missing in many charts. This limited our ability to perform a more detailed analysis. Third, some of the odd’s ratios in our multivariable analysis, such as older age (AOR 8.16, 95% CI: 2.268–29.342), had wide confidence intervals; this reflects the relatively small sample size and limited number of outcome events. These intervals reduce the precision of these estimates and underscore the need for larger, multicenter prospective studies to validate our findings and more accurately identify predictors of poor outcomes.

Conclusion

NASDH remains a common and impactful neurosurgical condition, yet most patients achieve good neurologic recovery when timely surgical evacuation is performed. This study identified low admission GCS score, initial body weakness, elderly age, midline shift, and prolonged length of hospitalization as key determinants of long-term neurologic outcomes. These findings highlight the importance of timely evaluation, optimized perioperative management, and structured follow-up to support neurological recovery. Strengthening these practices will essentially improve patient outcomes and reduce preventable morbidity.

Recommendations

To improve outcomes for NASDH at HUCSH, increasing awareness of factors affecting surgical outcomes is recommended. Prioritization of high-risk patients, close monitoring, and timely intervention are all needed to improve outcomes. Strengthening hospital data management by implementing an electronic medical record system would improve the accuracy and reliability of patient records and facilitate quality monitoring. In addition, future strategies to further enhance care could include the use of endoscopic middle meningeal artery embolization for multiple hematoma recurrence and the adoption of a closed subdural drain system to reduce preventable postoperative complications.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted after the institution review board approval letter was obtained from HUCSH’s department of surgery research ethical committee, which waived individual consent with registration number Surg /377/2022. The data was extracted anonymously, and confidentiality was assured at each step of data collection and processing. The study complies with the principles of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

Not applicable

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available due to patient confidentiality but are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with appropriate ethical approval.

Conflict of Interest

The authors note no competing interests.

Funding

The authors report no funding for this manuscript.